As a Black woman who fell in love with rock and roll at a young age, seeing and hearing Betty Davis’ music not only energized me, but moved me too. For a long time, I was told that my listening to rock music, often termed “the devil’s music” by members of my Christian community, was sinful and displeasing to God. Of course, I wouldn’t want to displease either God or those around me, so much of the rock music I liked, I listened to quietly. In addition, my music taste made me an outlier — most of my peers told me I was listening to “white music.” This couldn’t be further from the truth. With careful study over the years, I’d come to learn that rock music was born out of the Black community, and fused elements of gospel, blues and jazz. Even now, as I read more, I’ve learned that Black women have played an incredible role in shaping the tone of rock music — and many of these women weren’t credited for it, or paid enough.

Rock’s early days predate the civil rights movement of the 1960s, and artists like Fats Domino, Little Richard and Chuck Berry were early hitmakers. Black female artists like Big Mama Thornton and LaVern Baker were trailblazers as well. Many of the songs sung by these artists were covered by white artists to work around the racism and segregation prevalent within the music industry and the U.S. at large. A white artist’s cover of a song was usually more popular and seen as the “sanitized” version by white listeners. In these covers, gospel- and jazz-inflected adlibs and expressive lyrics were toned down.

The music charts and genre classifications of the 1940s and 1950s were segregated as well. Rhythm and Blues was the catch-all term for music made by Black musicians, and pop, rockabilly, rock and roll and country were among the broad range of terms reserved for music made by white musicians.

The advent of girl groups like The Shirelles in the late 1940s and 1950s allowed for Black women to be visible in rock and roll, but they were forced to conform to a set image and a set sound. Their influence still had a lasting effect, as many artists from the initial wave of British rock — The Beatles, Rolling Stones and others — all began their careers studying or covering songs by Black artists. They took Black vocal stylings and instrumentation, watered them down until they were palatable for white audiences and popularized them, just as their white American predecessors did before them. Behind the scenes, as author Maureen Mahon reveals in her book Black Diamond Queens: African American Women and Rock and Roll, Black women were the background singers adding texture to these hit songs.

Mahon also points out that Black women were exploited in rock — they had to behave and appear a certain way — soft, proper and ladylike, not too sexual. Yet they’re often fetishized in music. Black women have long been victims of stereotypes within music in the way they’re marketed, written about and discussed.

Though Black women and Black music tradition have long contributed to the sound of rock music, Black women themselves weren’t able to fully own who they were in music.

Think back to the Rolling Stones’ hit song “Brown Sugar;” the song immortalizes a Black woman who is sexual, who is seemingly supposed to be and is only seen her for her sexuality:

“Brown sugar, how come you taste so good? Uh huh

Brown sugar, just like a young girl should”

The song tells the story of someone sold into slavery in New Orleans, where the old slave owner was known to “whip the women just around midnight.” The rest of the song tells the story of interracial and clearly nonconsensual sex between the slave owner and a Black woman. Here, the Black woman is merely an object of sexual desire, exotic property not meant to be seen as human.

It’s due to this truth — the brutal history of how violently Black women were treated during slavery — that many Black women did not express their sexuality in their music. In Black Diamond Queens, Mahon notes that in the early 1900s, Black women often presented their femininity in a restrained, Eurocentric manner, seemingly because they had no other choice.

“This persistent denial of sexual expression has led African American women to maintain a deep silence around sexuality,” Mahon writes. “As historian of science Evelynn Hammonds notes, ‘One of the most enduring and problematic aspects of the ‘politics of silence’ is that in choosing silence, Black women also lost the ability to articulate any conception of their sexuality.’”

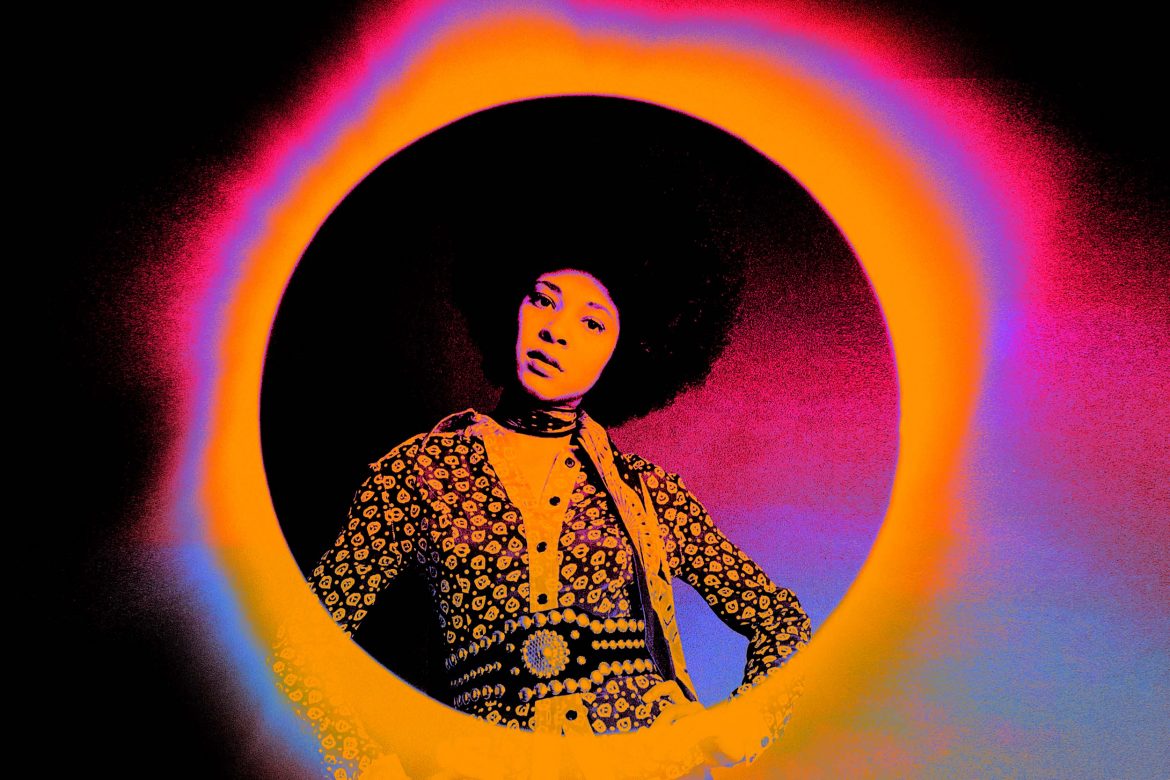

This is why Betty Davis is, without a doubt, an underrated visionary. Davis was born in Durham, North Carolina, but grew up in Pittsburgh, and she moved to New York for school. During her time at the Fashion Institute of Technology, she worked as a model and songwriter, as well as a co-manager of a dance club. During that time, according to Mahon, she utilized her music connections to help artists like the Commodores and others. In 1968, she married legendary jazz artist Miles Davis and introduced him to prominent musicians like Jimi Hendrix. Though they were only married for a year, it was through Betty that Miles Davis found the title of his 1970 album, Bitches Brew, and that in his own music, he began to experiment with fusions of funk and rock.

Betty Davis occupied a world that had a splintered view of Black women. She lived in a time when fighting for freedom meant putting on a uniform in hopes of breaking stereotypes. However, this uniform had its own price. Davis rejected the expectations of her role — she danced and sang from a place of deep emotion and paired her words with a confident sexuality. But in expressing herself authentically, she was shunned, considered too vulgar and barred from playing on TV.

Betty Davis released her self-titled first album in 1973. It’s hard to find reviews of the album, and her subsequent two records seem to have been released with little fanfare on the charts. According to a retrospective Pitchfork review from 2018, Rolling Stone Record Guide called her 1975 album Nasty Gal the work of a “black Marlene Dietrich,” referring to the German-American actress and cabaret star best known for portraying sexually liberated women. In this characterization, it’s clear that Betty Davis’ work was reduced to a comparison to white standards, and not the unique work of a Black woman who owned who she was. After her albums did not become commercial successes, Betty Davis was dropped from Island Records, and then went on to become incredibly private. She wouldn’t return to the public eye until 2017, when a documentary about her life and career was released.

In a New York Times interview around the time of the documentary’s release, she said, “I figured it would be better to have them cover me when I was alive than when I was dead.”

I can’t recall the first time I heard Betty Davis. I believe it was in high school, not long after I began to learn more about the Black community’s impact on rock music. In my memory, the context is vague, but her music is stark cand clear. I was either in school or at home, trying to learn more about women in rock music, and came across her name. The first song I ever heard was “Nasty Gal,” and I was floored. Here was a woman who sang with an authority and individuality deeper than I had ever heard before, who knew all of the influential players within punk and rock music — and who performed with platform boots and an Afro.

For someone who grew up in a religious, reserved environment that focused on the holy and remaining modest (not that there’s anything wrong with that, but it was stifling at times), hearing Betty Davis was a definite turning point in my own musical journey. Though I’m long past the days of wearing a safety pin in my ear among other strange fashion choices, I’m grateful to Betty Davis for the honesty and self-determination in her music, which still inspires me to boldly be who I am today.

Without Betty Davis and other women in rock music, it’s hard to imagine how we could have the music of Megan Thee Stallion, Rico Nasty, Prince and other groundbreaking mainstream artists. Even though she’s passed, her music must be passed on so the Black women of the future can remember their history and be proud of pioneers like her. And even though she wasn’t given her flowers during her time, she didn’t ignore her counterparts within music. In her song “F.U.N.K.,” she sang of her love for music and the Black musicians who impacted her — Stevie Wonder, Sly Stone, Ann Peebles and more. And, even in “They Say I’m Different,” she sang about her family and other artists that shaped her. She was unapologetically herself, and unapologetically Black — not reduced to her lively performances or the shock she caused white audiences. She was a true artist who carried a vital understanding of her culture, those who came before her, and the space she occupied.

As she did then, so we should do now: share her artistry and honor the Black artists we have with us now, especially those still coming up today. Own what makes you different, don’t dilute who you are to be more acceptable, tell your story — and don’t censor the nastier details.

Comments are closed.