In middle school, Larissa Oliveira found herself slowly slipping out of place in her small, conservative Brazilian town. Born in Itabaiana, Sergipe — the smallest geographic state in Brazil — she had attended Catholic school all her life, but her lessons were just now starting to lead to more questions than answers.

Her body was changing too — one of the most troubling and disorienting burdens of adolescence. The other girls in her grade seemed to pounce on her vulnerabilities. They called Oliveira the ugliest girl in the class and made fun of the hair on her arms. If she had been shy before, she was shrunken now, as if willing herself to be completely invisible.

“I didn’t speak — I was a really quiet, quiet girl,” Oliveira says now, at 26 years old, from her apartment in Rio de Janeiro. One of her hands is wrapped protectively around the tattoo on her wrist — two little words written in delicate cursive: riot grrrl. “And then, you know, I discovered this movement and it was life-changing.”

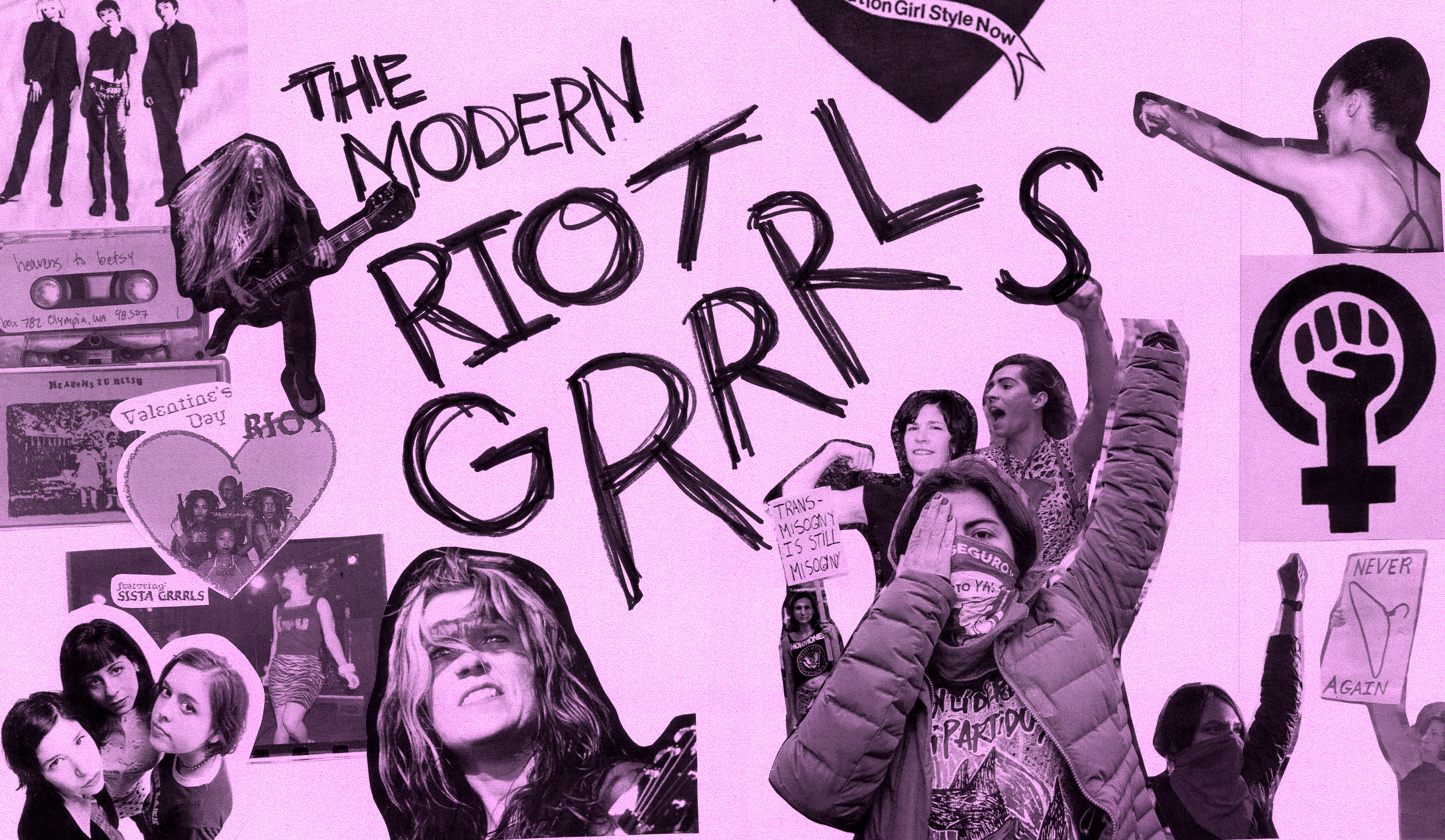

Riot grrrl is a counterculture feminist movement that began on the West Coast of the U.S. in the early 1990s, in parallel with the ‘90s grunge movement. Artists like Nirvana crammed three-digit audiences into dark music halls, a mob of listeners donning sweat-soaked flannels and black Sub Pop t-shirts with “LOSER” emblazoned across their chests. Bleached-blonde heads whipped back and forth to heavy bass and scratchy vocals while fans and musicians alike took to crowd surfing, limbs flying everywhere.

Almost all of the big names in these circles were men. Young girls were reduced to groupies — tossed around, harassed and frequently assaulted by other audience members. Riot grrrl music created a space in alt-rock for women to be everything they weren’t supposed to be — horny, angry, petty, gross and, most importantly, loud.

“It’s part of my survival,” Oliveira said.

She discovered the genre around 2010. Most major riot grrrl acts at that point — Bikini Kill, Bratmobile and Sleater-Kinney, to name some of the most famous — had broken up years beforehand. However, a decade later, the tone and lyrics of each song still resonated with 15-year-old Oliveira, who was otherwise navigating her sexuality and place in society alone.

Because Northern Brazil — where Sergipe is located — is one of the most underdeveloped regions in the country, Oliveira had little access to the internet, even in 2010. Still, she used every fleeting moment of global access to research the riot grrrl movement in the U.S. She devoured classic riot grrrl albums and read whatever books she could find. A rock record shop opened in Itabaiana, and she devoured every biography, memoir or music history book that was even tangential to riot grrrl.

And she started to change.

Her hair came down. Tied up in a bun on the back of her head for years, she started to wear her wavy dark brown hair down around her shoulders. And she picked up a tube of dark lipstick — like the plummy red lip she was wearing now — and started wearing bracelets, ones with spikes and ones that jangled when she moved her arms. While speaking about these small changes, she starts and restarts her sentences, blushes and laughs, trying to justify outward changes as though they might be seen as superficial.

“I saw these women being so expressive, and I wanted to be expressive too,” she says. “It’s so simple, but so complex at the same time.”

Oliveira was unlearning invisibility. She was unlearning the shrunkenness she had turned to for so long.

English had always fascinated Oliveira — she spent hours illuminated by the blue-white glow of the TV screen, watching English-language shows and movies. So, in Bikini Kill’s “I Like Fucking,” Oliveira heard her curiousities about sex in Kathleen Hanna’s cool-girl voice: I believe in the radical possibilities of pleasure, babe / I do, I do, I do. And in Bratmobile’s cover of “Cherry Bomb” — Can’t stay at home, can’t stay at school / Old folks say, ya poor little fool / Down the street, I’m the girl next door / I’m the fox you’ve been waiting for — she heard her own worries and resentment of the daughter her parents expected her to be.

Her Portuguese-speaking classmates, though, only heard unpleasant screaming and loud drums.

“It was a lonely, lonely place,” she said. “I had my riot grrrl moment by myself.”

Since its birth in the early ‘90s, the riot grrrl movement has been criticized for being exclusive, and many of the earliest riot grrrl acts did follow a certain mold: white, American, cisgender, thin, English-speaking. Because of this exclusivity, many critics of the movement — and even its founders — have said riot grrrl is dead, and rightfully so. Others, like Oliveira, are less sure. In the future these new grrrls blaze ahead of them, they are making an effort to reform an imperfect movement to include a wider range of people, rather than permanently close it off from larger audiences.

In 2015, amidst an emotionally abusive relationship, Oliveira picked up her headphones and started listening to some of her riot grrrl favorites — Bikini Kill, The Breeders, Slant 6, 7 Year Bitch — and, using an app on her phone, absent-mindedly made a collage of some of the members of each band. She gave it a title when she was finished: I wanna be your grrrl.

“I was like, am I making a zine?” she said, laughing. And then: “Okay, I am making a zine.”

Zines — mini DIY magazines — were a huge component of the movement in the ‘90s. Inside folded printer-paper booklets, zinesters pasted in their favorite lyrics and quotes from riot grrrl artists and wrote about how the movement had empowered or otherwise helped them. The riot grrrl movement was Kathleen Hanna performing with “SLUT” written in marker on her stomach, and it was Donita Sparks of L7 pulling out a used tampon onstage and throwing it into the rowdy crowd, but it was also this — high schoolers and college students sprawled out on the floor with fellow grrrls, surrounded by photographs and markers and magazine cutouts and glue sticks, with Slant 6 or Babes in Toyland or any of the other essentials blasting in the background, writing about vulnerability and finding strength in womanhood.

Oliveira eventually expanded her first collage into a whole zine, talking generally about the history of riot grrrl and her discovery of the movement. Recognizing how making zines could help her emotionally, Oliveira made the Instagram account @iwannabeyrgrrrlzine and continued creating. She now has a collection of eight zines and has contributed to a handful of projects by other people in the movement. Her later zines include manifestos on modern feminism, interviews with riot grrrl artists and poetry written by women all over the world. Soon after starting her zine project, Oliveira also found the courage to break up with her abusive ex-boyfriend and further avoid toxic men who put her down and make her doubt herself.

“This was a way to connect myself again with that powerful girl who had a voice and then suddenly was silenced.”

Oliveira has garnered an audience of over 2,500 followers on Instagram since she started her account. Aware of how language barriers kept her classmates from connecting with the movement as she did, Oliveira has also made an effort to make her activism as inclusive as possible. Every Instagram post on her account is written in Portuguese and English, as are her later zines, and her manifestos have focused specifically on dismantling white feminism and fighting for the rights of trans people.

“When I started making zines, I had a point to push the movement forward… I wanted to — and I think this is really important — to take what I learned and make something of my own.”

The five members of Sharp Violet — a modern riot grrrl band from Long Island — look on from different windows in a Zoom screen.

“Liz, that’s a great point about inclusivity because I was gonna ask about that,” I say. “[The riot grrrl movement] was criticized, like you said, in the ‘90s for being kind of skinny, white, femme, cisgender and American. What are some ways that you guys try to combat this stereotype?”

The call falls a little quiet and hesitant. All five members are white, cisgendered women, and though they may have asked themselves this same question before, it seems possible — probable, even — that they haven’t thought about it enough.

Lead singer and songwriter Liz itches the back of her head and breaks the silence.

“I mean, here we are, this basement band from Lindenhurst, Long Island, and people are hearing our music in Italy and in Mexico, in Australia,” she starts out a little cautiously. “So using our platform to bring awareness to issues that people are still facing in 2021, and being a safe space for people to come to if they, you know, don’t feel comfortable going to other shows. You’ll always have a safe space seeing Sharp Violet.

“We are allies,” she finishes sincerely. Jessica, the lead guitarist, nods slightly in agreement with Liz’s answer. Alli, the band’s rhythm guitarist, is looking past her webcam and into the back corner of her room. Marie, the bassist, continues to look up and away, deep in thought.

Sharp Violet’s desire to be allies, like many white artists who aim to be supportive of minority groups, is undoubtedly genuine. However, their caution demonstrates the difficulty for individuals to understand where to start when it comes to dismantling a global system of white supremacy and cissexism. There is no clear pathway to allyship, but instead miles and miles of baby steps that include uncomfortable conversations, deep introspection and unlearning social constructions you didn’t even know existed. In other words, what most white artists — and people in general — don’t realize at the start of their activism is that being an intersectional activist is hard and constant.

“Cissexism never sleeps,” says Anna Claudia, the musician and trans woman behind Brazil’s post-hardcore doom-noise act Umbilichaos. Despite being an intersectional feminist and a fan of riot grrrl music, she says she has always felt more like an observer of the movement, rather than a participant. Much like Oliveira, Claudia grew up in a small town and had little access to the internet for much of her life.

Claudia later quoted American philosopher and queerfeminism scholar Judith Butler: “If a woman doesn’t identify herself as a feminist, maybe that feminism doesn’t include her and it needs to change.”

If a woman like Claudia — who consumes riot grrrl music and makes music influenced by punk and her own experiences as a woman — doesn’t consider herself a riot grrrl, maybe riot grrrl doesn’t include her and it needs to change. But how?

Take, for example, Sharp Violet. Liz was right — they’re a basement band from Lindenhurst. Unlike Oliveira and Claudia, they are not bilingual and can only perform their music in English. The members of Sharp Violet, as mentioned previously, are also all cisgender and white — it would be wrong of them to speak on the experiences of BIPOC women or gender-nonconforming people.

So, without existing at the intersections of the people they seek to include, what really can they do? How do they dive into identity politics in a productive way, not one that further alienates them from different audiences or inadvertently harms the audiences they seek to include?

“I think we need to listen more, seek to know and understand other experiences,” Anna Claudia said. She’s speaking about riot grrrl as well as intersectional feminists as a whole. “Question more, instead of focusing on having ready-made answers for everything.”

The dilemma riot grrrl faces is one that gender theorists and race theorists have been struggling to answer since the birth of these disciplines. No one individual band or artist is going to solve the dual and opposing goals of intersectional feminism: How do we acknowledge inequity on the basis of race and gender while simultaneously arguing that the notion of race and gender are reductionary, meaningless social constructions?

Claudia’s suggestions, however, are a well-established starting point. As many students learn on their first day of a women’s and gender studies course, the personal is political. There is power in putting your personal truths into words. When we express our unique experiences through words, we are able to understand how social constructions affect us and discuss the feasibility of dismantling them.

If this theory seems inaccessible, look no further than Oliveira.

“Speaking. I am, all the time, speaking.” Riot grrrl gave her a voice when she had been silenced.

“Riot grrrl — what I love about it is that it’s a community,” Liz said, the other members of Sharp Violet nodding in agreement. “And helping people find their voices and to speak out against anybody who is not tolerant of everybody.”

“What would have been of those women without riot grrrl?” Claudia said, referring to the founders of the movement. Through talking with fellow grrrls at shows and reading zines, women were able to have conversations about things — sex, masturbation, beauty standards, queerness — that were otherwise shamefully locked away in their hearts. These kinds of discussions are feminism in action, not just theory. “It opened many doors to women from punk and hardcore to central discussions of feminism.”

What riot grrrl did for radical feminism in the ‘90s, it could do for intersectional feminism today, with a new emphasis on the voices of BIPOC women and gender-nonconforming people.

Considering the wave of right-wing conservatism washing over the globe, the new voices of this “dead” movement are quickly becoming more important than ever. In the U.S., Donald Trump’s presidency took American feminism back decades. His conservative Supreme Court appointees, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett, threaten access to safe abortions and the right of trans people to simply exist. It’s important for American activists to remain vigilant — if we have learned anything in the past few years it’s that however great our capacity for progress may be, our capacity to backtrack is just as strong.

Parallel to the United States’ conservative shift, Brazil elected President Jair Bolsonaro in 2018, setting the South American country back several decades as well. Bolsonaro, who has been described as the Donald Trump of Brazil, has cut funding from programs aimed at helping women escape domestic violence. These cuts were taken from an already meager program in the most dangerous region in the world to be a woman: Latin America. Within Latin America, Brazil had the highest number of femicide victims total in 2019, about 1,326 women. That’s more than 3 women murdered every single day.

Prior to Bolsonaro’s election, Brazil had been a relatively progressive country in terms of trans rights. As Claudia pointed out, a trans person in Brazil has the right to change their name and gender on legal documents without having to medically “prove” they are trans. This right to gender self-determination is not even established in countries like the U.K. yet, where you must receive a gender dysphoria diagnosis from a doctor and prove that you have presented as your gender for two years before you can pursue changing your birth certificate. While this right has remained intact, President Bolsonaro, who once said he would prefer a dead son to a gay son, has made clear that trans people are not wanted — and not safe — in Brazil.

“If identified as trans, I can die for that alone,” Anna Claudia said. “To be a lesbian will not be even mentioned. But if read as a cis woman, I could die for being a lesbian — and most days, just for being a woman, because we have very high rates of femicide too. In the end, Bolsonaro’s election just legitimized dominant ideas, but it was always like a civil war for us.”

The people on the front lines of this “civil war” of ideas are Larissa Oliveira, Anna Claudia, and the other grrrls worldwide who are, in many cases, fighting for their lives.

“This is not something that died,” Oliveira said. “I am sure millions of people in other places are going to have this moment, too.”

Considering the amount there is for women to scream about globally, she may be right.

Comments are closed.