Imagine there are 50 radios on a table. Jazz plays softly on one. On another, rock plays at a normal volume. On the next, pop blares. Each radio overlaps the others, one louder than the next.

This cacophony of noise is how Allilsa Fernandez describes her life with post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD, and psychosis.

“I’ve just learned to live with it,” the 35-year-old said. “The voices never go away.”

According to the National Institute of Mental Health, psychosis is a condition where a person has a loss of contact with reality – experiencing paranoia, visual hallucinations and hearing voices. About 100,000 adolescents and young adults in the United States experience their first episode of psychosis each year.

For much of her life, Fernandez’s mental illness has made ordinary tasks arduous.

Brushing her teeth was difficult because she couldn’t recognize the person staring back at her in the mirror. Fernandez avoided driving because she was afraid she might hit someone. A 30-minute homework assignment would take her five to six hours because she had to reread the same sentence over and over to absorb the information.

Going to the bathroom was almost impossible. Because of her paranoia, she felt like everyone was listening to her. While sitting on the toilet, she could hear her neighbors’ conversations and was terrified that they could hear too. She refused to go. It came to a point where she considered bringing a bucket into her bedroom to urinate in.

When she was a junior at Stony Brook University in 2008, she experienced a life-altering injury. Fernandez was living in a small second-floor apartment in Port Jefferson, which she shared with two other tenants. She was organizing her room and had to store some extra belongings in the attic. When she got to the top of the staircase with some luggage, she slipped on a wooden beam and fell through the sheetrock.

Her body dangled from the ceiling; the ground was 10 feet below. What was a five-minute ordeal felt like an eternity to her.

“I had two options, either I drop and end up in critical condition, or pull myself out and save my life,” Fernandez said.

She managed to pull herself out, but the incident left her immobile for months and she had to walk with a cane. Fernandez withdrew from the university and would not return for another seven years. She used this time to focus on healing both physically and mentally.

Fernandez got involved in Second Life, an online video game similar to Sims. Between 2010 and 2014, she met many individuals with mental illnesses through this medium. She attributes her recovery to the support she received from her peers.

“When I was hearing voices, they told me to put headphones on and listen to music,” she said. “When I felt I was dissociating, they told me to grab ice and hold it, so the shock would snap my brain back. I learned those [rehabilitation methods] from peers, not from professionals.”

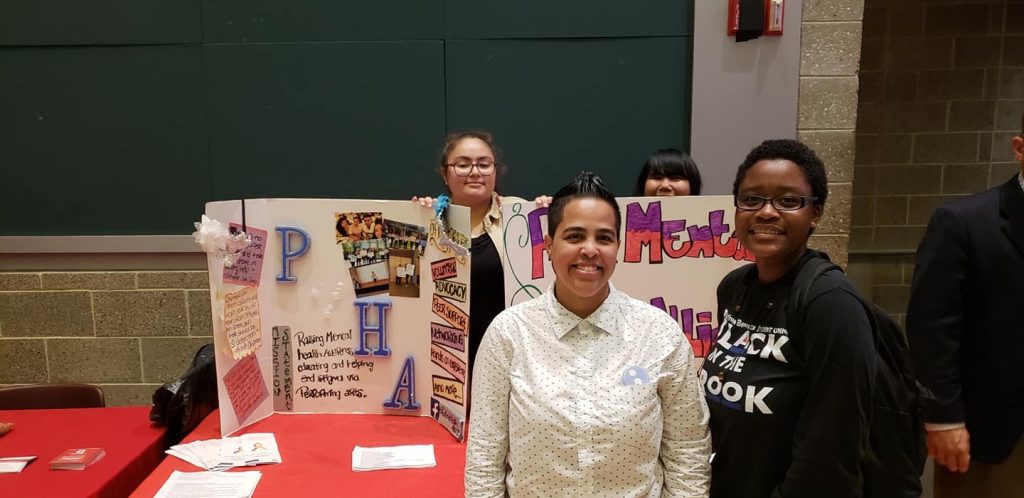

When Fernandez returned to Stony Brook after her hiatus, she wanted to create a similar environment to the one she experienced through Second Life on campus. Two years ago she founded Peer Mental Health Alliance, PMHA, an organization that provides peer-to-peer support for students struggling with their mental health.

“Allilsa does everything she can to diffuse and disarm the stigma against psychological conditions,” the current president of PMHA, Alex Sindo, said about her predecessor, who she describes as a mentor and a friend. “She is always doing whatever she can for the community.”

Before PMHA, Fernandez felt that the pre-existing mental health-related clubs did not fulfill her needs. This alliance does advocacy work, connects students to resources on and off campus and participates in rallies.

“Mental health is not something to be ashamed of,” she said. “So I decided to create a club where instead of people having to come to us, we were going to go to them and normalize the conversation.”

One event, in particular, was really impactful, in Fernandez’s opinion. Students were given headphones that played voices at different levels all at once. During the simulation, they were asked simple questions: What is your name? What is 2+2? What state are we in? Ninety percent of students had to take the headphones off, because they found it too challenging.

“You could take off the headphones, but other students don’t get that opportunity,” she said. As a person who experiences psychosis, these symptoms were all too familiar. “It’s what they deal with and live with on a daily basis.”

Fernandez not only advocates for mental health at school, but also within her family.

Her cousin, Arlene Perez, describes her family as “old-school Dominican.” They grew up in Brooklyn and were raised Catholic.

“[Fernandez] explained to our family, even our elders, that mental health is just as natural as high blood pressure and diabetes, and can be treated with therapy and support,” Perez said.

At that time, Fernandez’s mom fell ill and she became her caretaker. She was only 15, the oldest of three, and had to grow up quickly in order to support her family.

“She’s a survivor; she has endured a lot of pain,” Perez said. “My cousin is graduating college, when she was set up to be medicated for life at home to do nothing with herself.”

Fernandez finished her bachelor’s degree in psychology in December, with magna cum laude. After more than a decade since first enrolling in Stony Brook, she is finally going to walk during graduation in May, what she calls “a dream come true.”

Comments are closed.