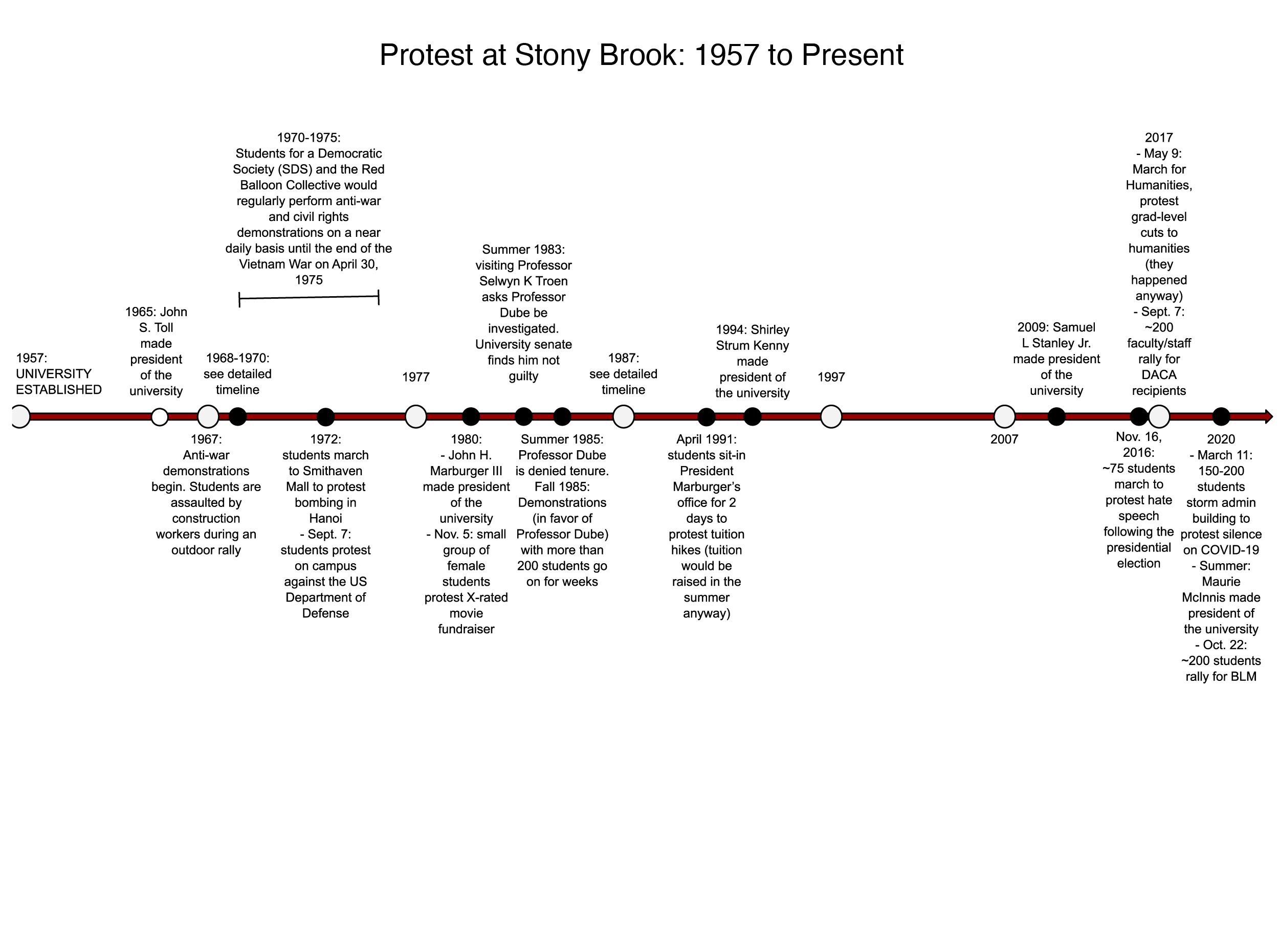

If you ask a Stony Brook University student about activism on campus, they’d likely have little, if anything, to say. To Mitchel Cohen, a student from 1965 to 1975, that reality is hard to swallow. Just half a century ago, Cohen’s days were punctuated with protests on what, according to him, was the most politically active campus on the East Coast. As it turns out, the history of Long Island’s “sleeper campus” is littered with smashed windows, smoke bombs and student arrests.

In Stony Brook’s early years, the university administration juggled a laundry list of internal issues and student complaints. As a rapidly growing university, construction was the soundtrack of student life and living conditions were poor. Roaches scuttled along the tile floors of overcrowded, hastily built dorms, and a student was even vaporized in February of 1973 when he fell through an open manhole into the steam tunnels (his death is commemorated by the Science Fiction Forum on Sherman Raftenberg Day in early February every year).

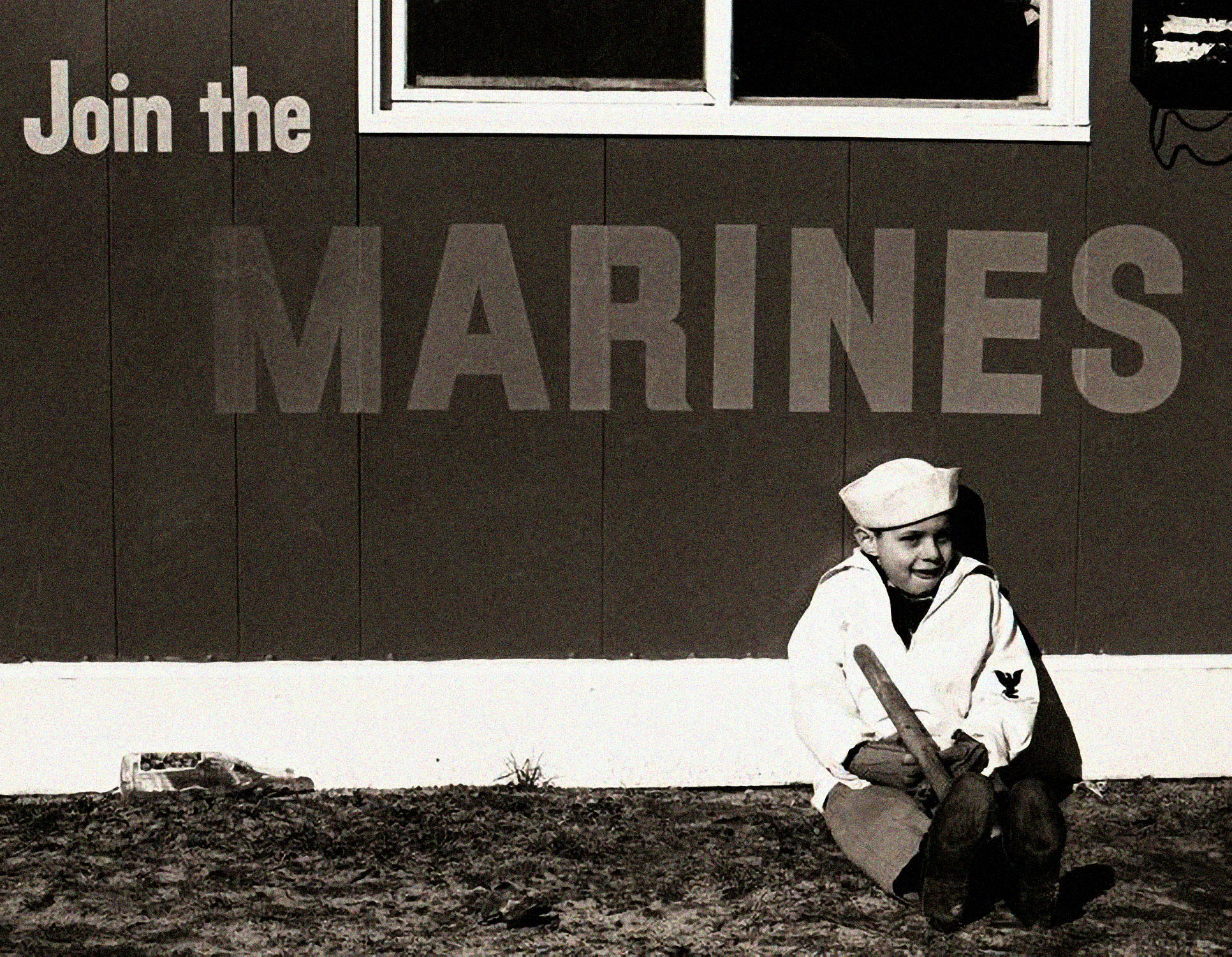

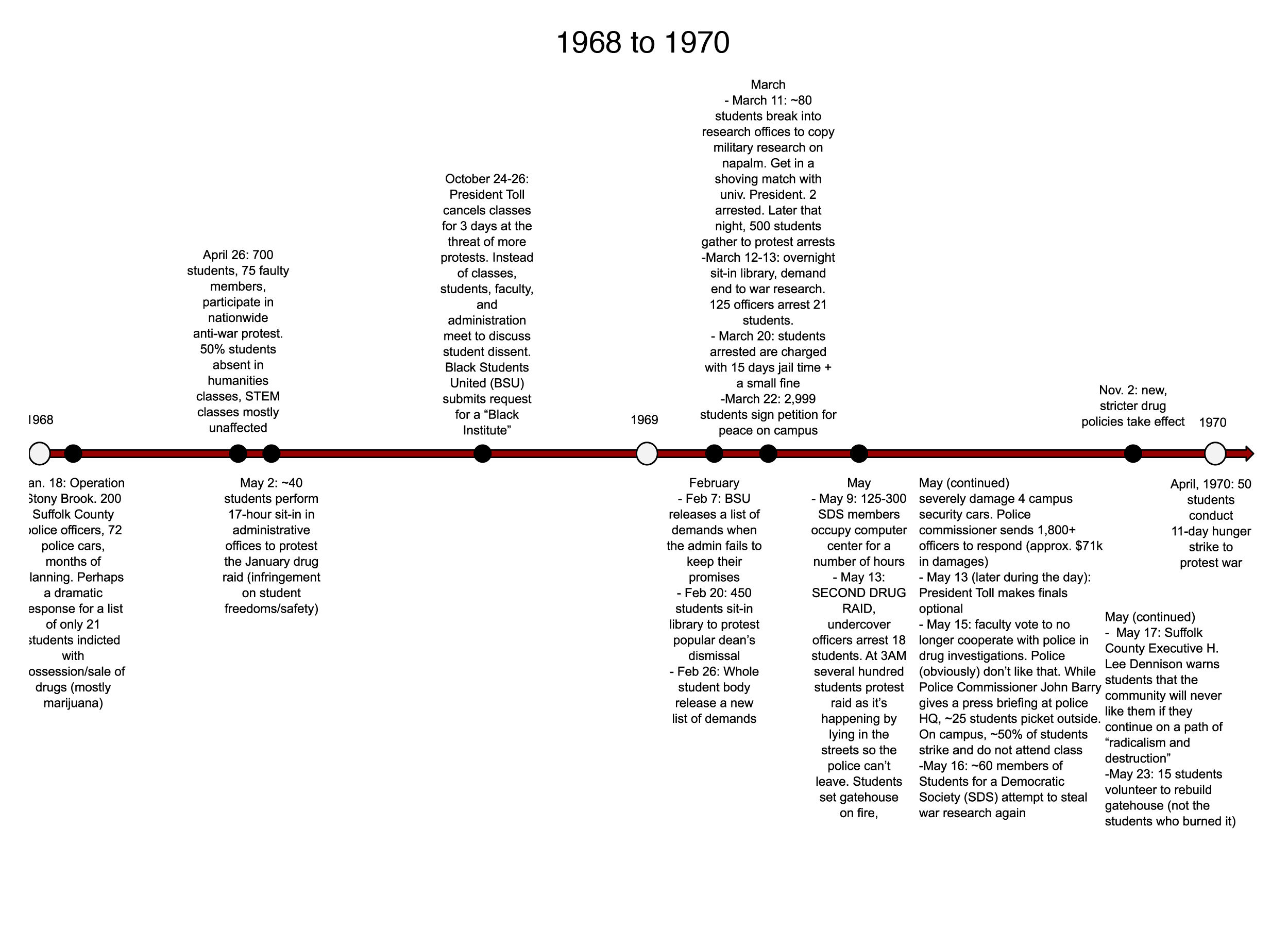

The diversity of the student body was a sore spot for surrounding communities as well. Decades before the university was established, 30 minutes south of Stony Brook in East Islip, the KKK held what was at that point one of the biggest Klan rallies in history (with somewhere around 25,000 members in attendance). Another 30 minutes east from the university, and you’ll find the sleepy little town of Yaphank, which was home to a Nazi summer camp that mirrored the Hitler Youth in the 1930s. Deep-rooted white supremacy on Long Island paired with a university that actively recruited students from different racial and ethnic backgrounds created a tense town-gown conflict, which to some degree, still exists today. The administration scrambled to improve the university’s relationships with surrounding residential communities, but over-policing and bad press would continue for decades. One of the clearest examples of borderline militant police use at the university would be Operation Stony Brook in January of 1968, where months of planning from the Suffolk county police department resulted in one of the largest drug raids in American history (in terms of officers involved).

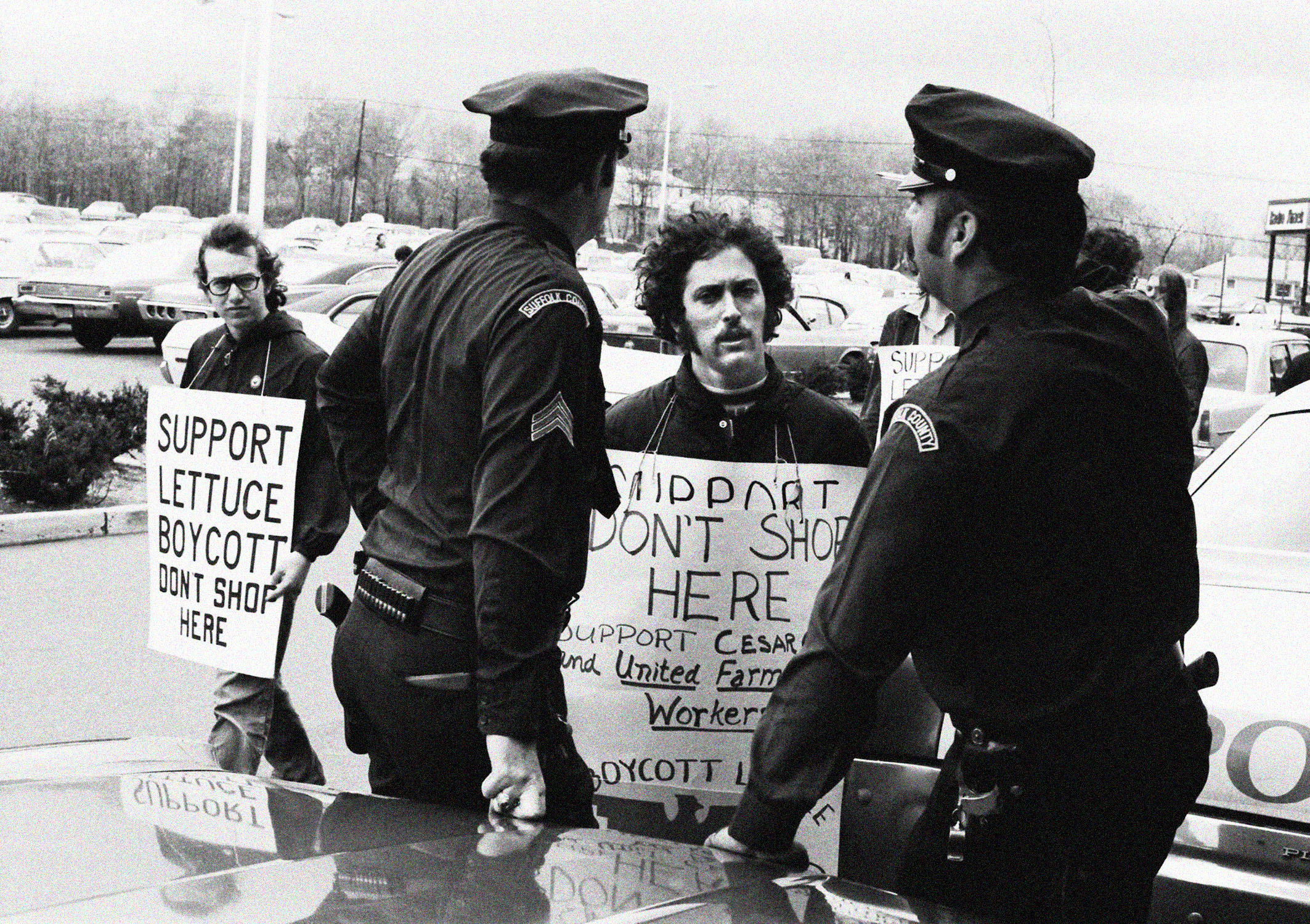

These issues and more, plus the nationwide backdrop of the anti-Vietnam War movement and the end of the Civil Rights Movement, cultivated a generation of students who were not afraid to demand change — and demand they did. Cohen said that he and other members of the Red Balloon Collective, a prominent student activist group on campus at the time, got creative with their tactics. To protest the university’s collaboration with the military during the Vietnam War, members of the Red Balloon Collective broke into the graduate student research offices and stole war-related papers written by students, professors and even the president of the university himself. Cohen laughed as he remembered students crawling through the ceilings with stolen papers right over police officers barricading the other side of the door. When the campus was covered in mud due to constant construction and deforestation, students dumped buckets of it in the library and administrative offices. Cohen even described interrupting a SUNY Board of Trustees meeting to present then-university president John Toll with the “Prick of the Year” award. His trophy? A several foot tall penis.

“A lot of the movement in the past eight or nine years is worried about being marginalized,” Cohen said, referring to a slew of so-called radical left ideas, like Black liberation, gay and lesbian rights, and women’s liberation. “We didn’t worry too much about that.” While politicians today might water down their ideas as to not scare people off, Cohen and the Red Balloon Collective maintained their radical politics while attempting to find understanding in others through humor and art. “We were serious about what we were doing,” he said, “but we didn’t want to do it in a dead serious way.”

It’s hard to say exactly how and why the passion for activism on campus has diminished so greatly. Cohen said the university administration has always made a concerted effort to quiet students by taking away independent community spaces. When he was a student, they closed a cafeteria run by students in an effort to keep activist groups from meeting there, and many of the residential quads built in the time since Stony Brook’s wildest days were constructed to be “protest-proof” (consider Kelly Quad: are there any open spaces for students to gather?).

Karl Grossman, a former reporter for the Long Island Press, was handpicked to cover Stony Brook in the late-1960’s in an effort to offset some of the ruthless negative press the university was getting in response to student protests and alleged drug use. As a “sensitivity reporter” he was able to get to know the university intimately over the course of several years, both the administration and the students. “The vision of Stony Brook was to become the Berkeley of the East,” he said, “It was not intended to be like a CalTech.” He explained that as the educational focus of the university shifted more towards STEM and farther from what it was meant to be, activism seemed to fizzle out fairly quickly. This has some validity — many of Stony Brook’s early protests had major support from humanities students and were largely ignored by those studying science and math (perhaps because their courses are too loaded to take time out and focus on protesting). According to Grossman, the university flourished the most under former President Shirley Strum, who came from an English background and bolstered the humanities programs. Former President Strum brought the university closest to what Grossman believed it was intended to be, and the happiness of the student body reflected those changes.

Current students also have their own theories about the lackluster vocal activism. “Vocal” is the key word, because according to students Kyria Moore, Nia Wattley and Oreoluwa Adewale, performative activism has become a big problem. “I wish there would be more action,” Adewale said, “because a lot of people on this campus were posting over the summer.” She was grateful and humbled by the rally’s turnout, but had also taken notice of the gap between the number of people she saw posting about George Floyd in June and the number of people who actually marched alongside Black students in October. When asked about whether or not the university was politically active, Wattley paused for a moment and said, “Not out loud… maybe on Twitter, maybe on Reddit, but when I’m walking around, I don’t feel like it’s politically active.”

Wattley and Moore are members of the Black Student-Athlete Huddle, while Adewale is president of the university’s NAACP branch. The two groups collaborated to put on October’s Black Lives Matter rally on the Staller steps, and Wattley, Moore and Adewale emerged as the student leaders at the helm of the protest. With more than 200 students in attendance, they managed to pull off the biggest student-led protest on campus in recent history.

When discussing October’s rally and the potential for more in the future, Moore expressed her excitement, saying, “because there hasn’t been prominent protests on campus that I’ve seen… it inspires me and other students to make change and be seen.” Wattley was also very excited about the potential for more activism. “I love to see students with voices sharing the things that they’ve learned, their stances, their opinions with others.” Equally enthusiastic, Adewale courted other student groups for future demonstrations, saying, “the NAACP is always willing to collaborate.”

Collaboration may prove to be one of the most important tools budding Stony Brook activists can use. Back in Mitchel Cohen’s time, all the issues the students fought for — Black empowerment, peace, women’s liberation, gay and lesbian rights — were connected, and all these groups supported each other in their advocacy. Cohen encouraged current student leaders to put an emphasis on unity. Too many people, he said, fight for others, causing an existential disconnect. He said he wished that he and his fellow “comrades” had created circumstances in which people could realize they are fighting for themselves as well as other people. As he said, “you cannot be free until everyone is free.”

Hopefully, student activists here at Stony Brook find that advice useful. It is up to the students whether the October rally is the beginning of something bigger. “The wind’s at their back,” Professor Zebulon Miletsky of the Africana Studies department said in reference to budding activists. As someone who has studied civil rights and Black power movements, Professor Miletsky said he believes the knowledge of activists long graduated can impact current students.

“Each new crop needs to find an entry point,” he said. He believes this generation has found theirs.

Comments are closed.