If there’s one thing today’s older generations love, (besides posting Confederate flag minion memes to Facebook) it’s lazily pathologizing young people. This isn’t new, of course. Despite slight modifications, complaints about “the youth” have remained consistent since the ‘60s: Kids are narcissistic, entitled, overly sensitive, strangely consumed with technology and the opinions of others, and lacking in motivation. As always, stereotypes, aside from being incomplete and often wrong, are painfully, crushingly, fucking boring — procedurally generated broadsides that both illuminate and prove nothing.

But I guess we shouldn’t be surprised.

Thankfully the tepid, superficial non-analysis of younger generations isn’t entirely lost on our wilting intellectual class. CUNY political theorist Corey Robin recognized this blindspot in our punditry, and in a blog post from July 2017, called on writers and journalists to write a definitive account of the millennial/Gen Z generations. In the post, Robin recalls the excellent “The American Earthquake,” a rigorous journalistic account of life during the Great Depression. In the book, journalist Edmund Wilson set out across the country interviewing Americans of all races and classes on their experiences during the 1930s financial crisis and its grim aftermath. Robin, summing up a Washington Post article on economic precarity, noted what he found to be telling about the attitudes of bourgeois media towards millennial saving habits:

“Second, that the Post thinks millennials earning $40,000 a year have tons of extra disposal income to sock away for their futures seems risible. Given rents and job precarity and student loans that have to be paid off, it seems totally rational to me that a young person in today’s economy would want to be assured that they’ll have money for food and rent come next month,” said Robin. “Better to keep it in the bank than tie it up in a long-term index fund or whatever. Having the money near at hand seems perfectly understandable.”

In his conclusion, Robin defines the Millennial Earthquake in much the same way the Earthquake of the 1930s was defined: by the economic precarity resulting from a financial crisis and a long downturn in capitalist institutions. Fair enough, none of that is untrue, so to speak, and Robin is certainly one of the most thoughtful intellectuals writing today. But just as many a listicle ultimately proves incomplete, so does the redefining of the American Earthquake as one of simple economic relations. There is something else at play here. So what is it?

The current political economy of the United States is grotesque and unjust, particularly for young people. Millennials are worse off than their parents despite higher educational attainment and aptitude, while drowning in student loan debt and multiple jobs. These sources of hardship, of course, break down along racial and gendered lines, garnishing the indexes of domination in society with an additional layer of injustice. From this point of view, the conception of the Millennial Earthquake as one of simple economic conditions seems to hold water.

But what about the other ruptures?

The condition of being born between 1982-2000 is the condition of being raised in an era of endless, shadowy war, perpetuated by an imperial power that no longer feels even the most superficial need to justify its genocidal incursions.

It is the condition of living through mass shooting after mass shooting, often carried out by those whose generational makeup is consistent with ours. No meaningful remedy ever arises from such massacres, which are framed as “tragedies” but are so often concrete results of legislative neglect. The same can be said for our water crises, extreme poverty metrics and austerity-induced tower-fires across the Atlantic; the preventable is clutched and molded into the fatalistic by those whose only identifiable function is the middle-management of our expectations. Perhaps this is the Millennial Earthquake.

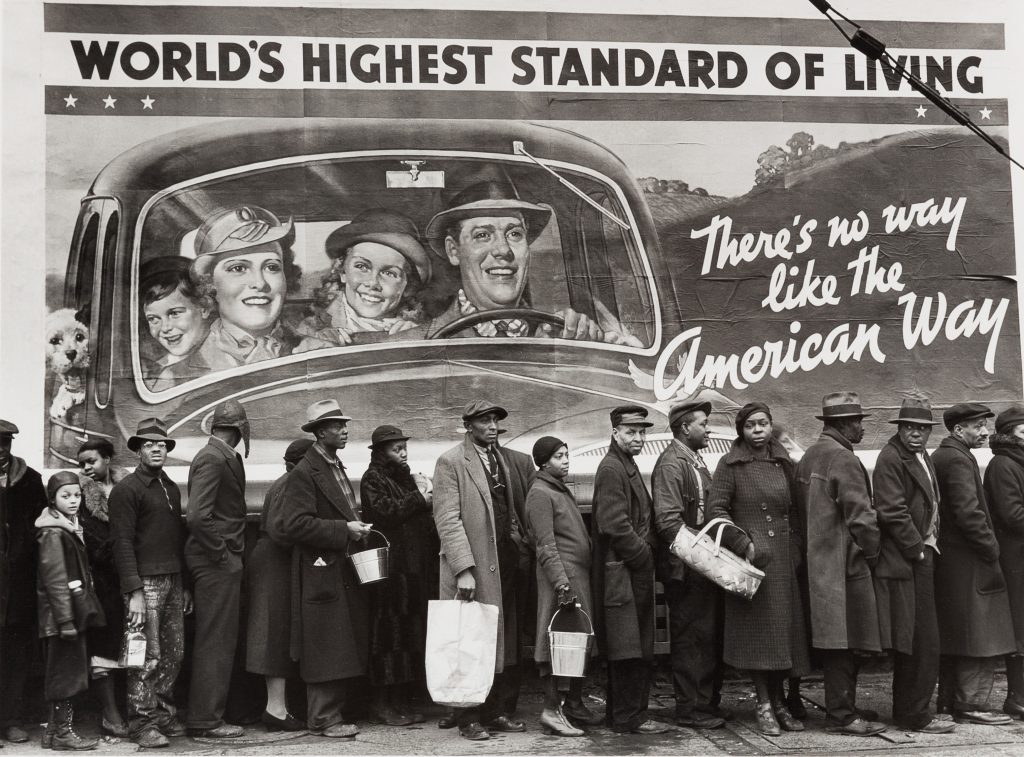

Or maybe there is no “one” American/Millennial Earthquake. In 2019, as it stands now, our most salient characteristic seems to be our inurement to crises; the semi-regular tremors that seem to shake the fabric of our institutions to the core but leave them intact, somehow, with plates remaining stagnant along the fault lines of our systems’ contradictions.

In fact, our momentary shocks that end up producing nothing but ideological inertia seems to be the most telling aspect of all. The preservation of an existing way of doing things, in the face of what seems to be a rebuke of its merits, results in the spiritual whiplash of those who are privy to it. While the vision of the 21st century American Earthquake as a Wilsonian tale of economic strife is insufficient for our current condition, such failure to change existing ways at least seems to mirror the dark resilience of certain economic institutions, particularly our own.

The late economist Hyman Minsky recognized this, and inadvertently provided what is perhaps the best intellectual framework for understanding our current Earthquake.

In his landmark account of the inherent instability of financial systems under capitalism, Minsky broke with normal Marxist prophecies wherein one grand, spectacular crisis would bring the entire system crashing down. Instead, Minsky accidentally levied the astute observation that, with every bailout, with every stitch that rendered a wounded system whole again, the very foundations of that system were therein reinforced and justified. This has come to be known as “The Minsky Moment” among academics.

Mike Beggs, in a Jacobin profile of the influential, yet under-cited economist, described it in the following:

“Every time the Federal Reserve protects a financial instrument, it legitimizes the use of this instrument to finance activity. This means that not only does Federal Reserve action abort an incipient crisis, but it sets the stage for a resumption in the process of increasing indebtedness — and makes possible the introduction of new instruments.”

Thus, the 21st century American earthquake is the extension of the Minsky moment to all corners of life: Every time a high school responds to the newest mass shooting by arming security guards and teachers, it legitimizes the self-imposed inertia put in place by our lobbyist-beholden legislature, burrowing us all deeper down a rabbit hole of routine mass-violence. Every time a neoliberal think-tank responds to the newest apocalyptic climate change report with yet another call for a weak cap-and-trade program, it legitimizes the notion that there really is no alternative to market half-measures, even in the face of the end of a habitable planet.

You could thus break the two American Earthquakes down along Minskian and Wilsonian lines. Our current Minskian earthquake differs from Wilson’s Great Depression in several subtle, yet stark ways.

When Edmund Wilson was writing in the 1930s, he did so during the drafting and implementation of the New Deal, a political program rife with exclusionary measures that nonetheless birthed something new in the ashes of the old; the New Deal was at least a response to an Earthquake. All we’re left with now is, well, nothing — more earned-income tax credits, more corporate subsidies, more unenforceable background checks and cap-and-trade programs, more borders and more walls. The past is dying and the future cannot be born: The American Earthquake.

In observing all of this, maybe it is not so surprising that older generations love to bash the young. As anthropologist David Graeber noted in a Baffler piece on the failed utopias of yesteryear, chief among the dying pathologies of the American imagination is the belief in future progress of any kind. Every source of resentment one has toward the young could be seen as the inevitable result of the older’s failure. In every condescending article about a Gen Z child addicted to iPhone games, the baby boomer sees in them the failure of their own generation: “We were promised flying cars and high-speed cross continental travel, and all we’re stuck with are these fucking apps,” they think. In every piece about some supposedly novel sense of narcissism or entitlement among millennials, the olds see a mirror unto themselves: a generation raised to believe they were different and transgressive, but retreated into conformity and a shallow individualism around the time of the first Volcker shocks. What a baby boomer or Gen X-er feels toward the young is not resentment, per se, but fear. Fear that nothing ever changes, fear that every earthquake neither forces nor produces something new.

Maybe we’ve been living through the earthquake longer than we’d all like to admit.

Comments are closed.