When you first meet Dewayne Wrencher you wouldn’t necessarily equate his sunny disposition with his seemingly poignant art style. “People say ‘who’s it for, like who’s your audience?’ You know, they’re really trying to put you in that box. I always tell them its for me first,” Wrencher explained, mulling over his artistic career here at Stony Brook.

The 30-year-old Master of Fine Arts candidate and self-proclaimed “native born black” artist has spent the last three years on campus exploring themes of racial identity through his various works and exhibitions.

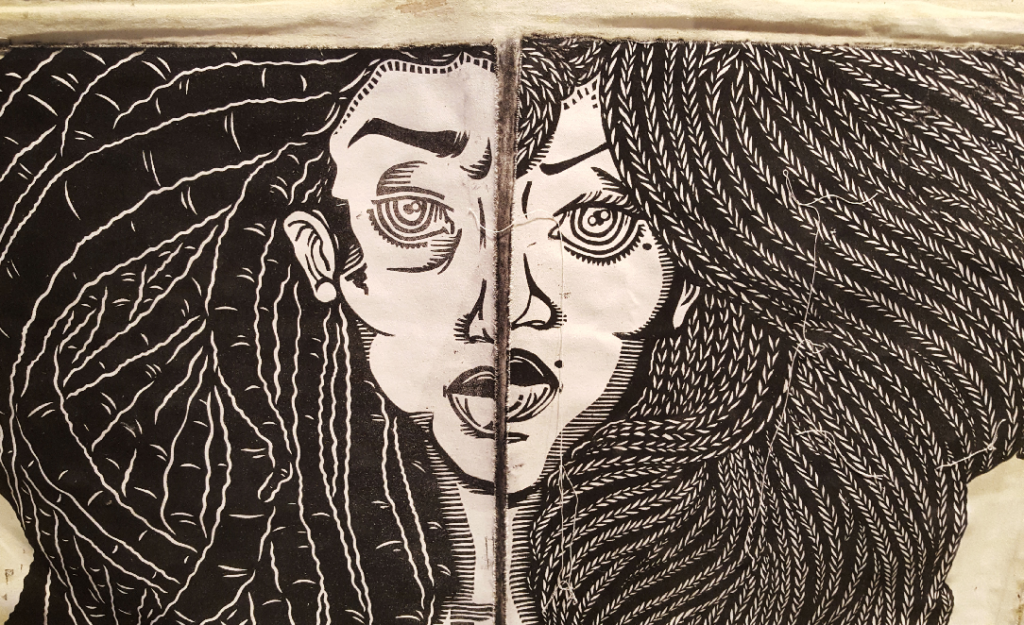

His detailed depictions of black individuals in exhibitions like Black What? and Hair Theory keep your eyes wandering around the ebbs and flows of the line work. You only need to share a few words with him to get how an outgoing personality like his, gives way to such art.

Born on the southside of Chicago, Wrencher’s passion for art began early in his childhood. “My oldest brother, he used to draw. This man used to be mad gifted. And I was like, man let me get closer to my older brother,” he said. “And I was like man you gotta teach me how to draw. So he taught me how to draw and that was like my introduction to actually using pencil to paper and just like sketching something out.”

What started out as a hobby between brothers eventually grew into a family affair with his twin brother, sister and younger brother following suit soon after.

“We would do door-to-door sales and we would sell images. It was really sweet,” Wrencher began. “Drawing was our way of getting the family together without being a problem.”

While things on the inside were going well for Wrencher’s family, the situation on the outside wasn’t as good. Incidents of street violence started to become more and more common until the threat finally hit close to home.

“My uncle, her older brother, he was murdered. It was like she had too many boys to raise in this environment.” After that moment Wrencher’s mother made the decision to gather up him and his siblings and leave the city. “I always thank her for that, because you don’t know how you could’ve turned out.”

The family hopped around different parts of the tri-state area, never staying too long in one place. With each and every location, a young Dewayne absorbed the world around him, taking note of the little differences in every person he saw.

“You really got to see the way people would interact with each other and then you become like a person that watches people. And then you’re like hmm, that’s interesting.” Against the constantly changing backdrop, he started to get a better picture of the greater area and himself. Unfortunately, along with that came some less than satisfying experiences.

“I remember some time ago when I was younger, we were living in Aurora Falls at the time, there was a group of people that considered themselves the KKK,” Wrencher said, recalling the threats his family received. “We went into defense mode but something stopped me because I was wondering like why the hell is this not like a surprise to me? Why is this like the norm? Why are we acting sort of like on impulse as if this is something we should’ve expected.” In the subsequent years to follow, he would go on to explore those feelings extensively.

When the time came to head off to college, Wrencher spent some time attending Western Technical College in Chicago before transferring over to the University of Wisconsin-Lacrosse. After a brief stint as a business major, he finally took the plunge into art after taking an introductory printmaking class.

At the heart of Wrencher’s work is the constant need to illustrate a clearer picture of what it means to be black in America. The hair, eyes and noses of his characters are exaggerated giving each face a natural vibrancy without the need for color.

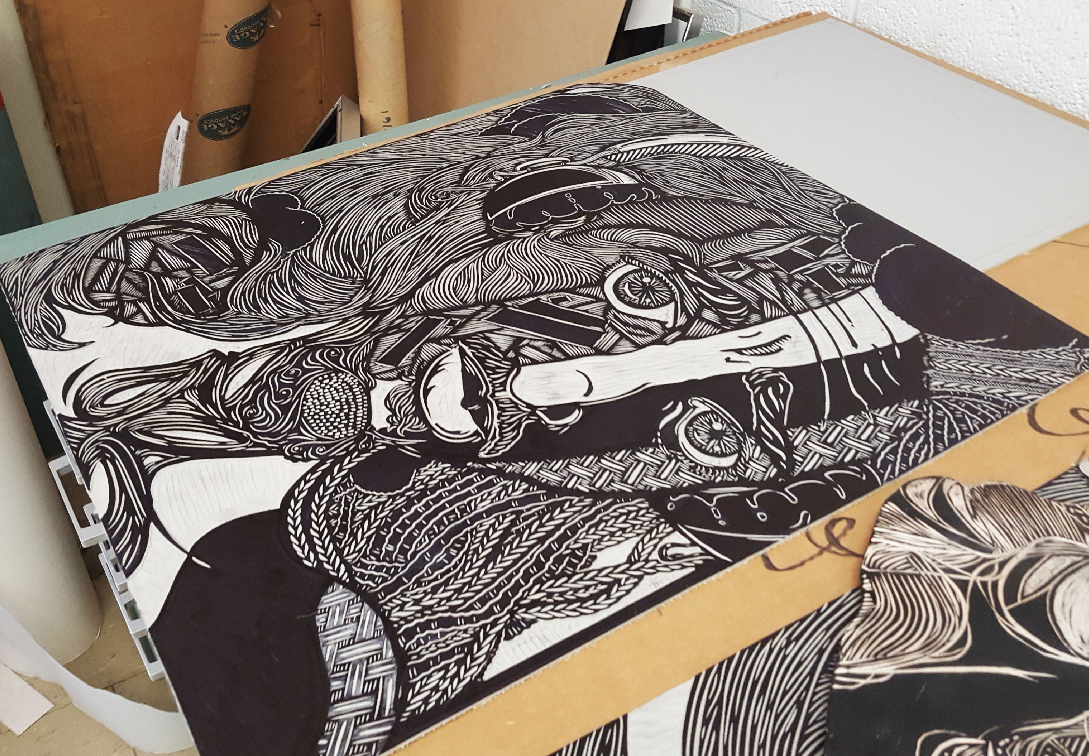

Printmaking has remained Wrencher’s medium of choice over the years because of the aesthetic and history behind it. The process, which uses images cut on blocks of material like linoleum as imprints, has a centuries-long history of giving voice to underrepresented groups. “Here’s the thing about printmaking, it was initially used as a way to educate the poor man. And I’m all about education obviously. It’s just like in me.”

Due to the process itself, each print carries with it distinct marks that make it its own. “You can literally see every mark you make. This is definitely made by hand.”

Along with three other MFA candidates, Wrencher’s latest works were featured in the BODIES exhibit that ran through most of April at the Zuccaire Gallery.

“Working with Dewayne and the other MFAs was terrific,” Karen Levitov, director and curator of the gallery, said. During the fall semester, Levitov met with Wrencher and the other grads to help plan out their final thesis projects. “Dewayne wanted to create a very large piece, which is great since we have 24 foot ceilings and huge walls. He created a piece made up of four large canvases, each with several linocut prints on canvas attached.”

Much of his final work was guided by the information he gathered interviewing nine people on how they perceived their own racial identity. What resulted was a deconstruction of umbrella terms like “African American” that seek to ignore the diversity within the black community in favor of an easy to get behind label.

The conversation isn’t one sided. Just as much work is asked of the viewer both symbolically and literally. One work made up of a series of questions designed to make you mindful of your own background, also had a space at the bottom for anyone to contribute their own questions to the conversation.

Over time, Wrencher has learned to balance the fine line between observer and participant. “The difference now is that it seems like it is so political now so it seems like a lot of people want to engage in this conversation, which is great, but you really can’t force somebody to do something. Like they have to want to engage.”

Wrencher credits civil rights era sculptor and graphic artist Elizabeth Catlett as his main influence; her multifaceted portrayals of the black 20th century experience served as the foundation for Wrencher’s work.

“That’s where I got my lips from cause I could not figure out how to do these lips,” Wrencher mentioned. “She talked about the idea of the black artist. She was like you have some people that just like to say they’re black artists whenever it’s like convenient, and she was like you have the true black artist where they understand that there has to be a level of education, activism, something in the work other than just the work.”

As a part of his time in the MFA program, Wrencher currently teaches ARS 274: Introductory Printmaking on Tuesdays and Thursdays. “I’m like, okay I have the gradebook here but I try to develop a relationship with them so like if you have any issues come in and let’s see if we could solve those issues. I’m trying to make sure that you have some work that you can add to your portfolio.” Wrencher hopes to continue teaching later in the future.

However, shortly after he graduates he plans on gathering up his work and going on a traveling exhibition that he plans on calling Sense of Agency. “I’m trying to get more black males to understand that if you want to be powerful the best way to be the most powerful is to have more control over self,” he added about the planned workshop.

Wrencher wants to try his best to give as much he takes from his surroundings, which remain his main source of inspiration. “If you’re a person and you’re gonna be an artist, you have to take responsibility for the images that you create because they can have a positive and or negative effect on whoever sees it. You have to take responsibility for that.”

Comments are closed.