In 1636, a farmhouse on one acre of cow pasture became America’s first establishment of higher education. As told in The History of American Higher Education by Roger L. Geiger—distinguished professor of Education Policy Studies at Pennsylvania University—the Great and General Court of Massachusetts Bay Colony, hoping to establish a college comparable to the universities of their former country, an Oxford or Cambridge of the New World, gave 400 pounds to what would become known as Harvard University.

Seven years later, in 1643, a pamphlet titled “New England’s First Fruits” published a passage recalling the university’s conception: “After God had carried us safe to New-England, and wee had builded our houses, provided necessaries for our livelihood… one of the next things we longed for, and looked after was to advance Learning and perpetuate it to Posterity…”

373 years later, these words still are inscribed on Harvard’s gates, and politicians still argue about their meaning.

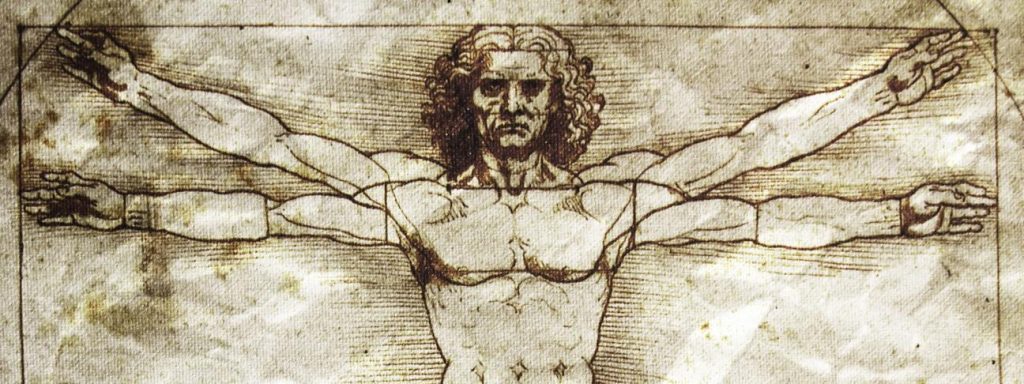

But before diving into today’s arena of politics, a look at the politics of the past reveals a thread to the education debate similar to what we see today. The education philosophies of Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin reveal that the founding fathers did not always see eye to eye on the issue.

Thomas Jefferson praised education as a way to preserve the democratic ideal and, for this reason, believed education should be free for all. He laid out these thoughts in a letter to British scientist Joseph Priestly in 1800. Education, he explained, cultivated not only a person’s intelligence, but also their moral sensibility. In 1802, Jefferson founded the University of Virginia on these principles, inviting students to “drink of the cup of knowledge.”

Benjamin Franklin, however, disagreed with Jefferson. The Renaissance man advised against spending too much time in lecture halls, preferring self-education to traditional schooling. In his autobiography, Franklin suggests the irony of his receiving honorary degrees from Harvard and Yale, even after dropping out of school at age twelve: “[T]he College of Cambridge of their own Motion, presented me with the Degree of Master of Arts. Yale College in Connecticut, had before made me a similar Compliment. Thus without studying in any College I came to partake of their Honors.”

Like Franklin, 11 out of 44 United States presidents never earned a college degree, a list that includes George Washington and Abraham Lincoln, as reported by education specialist Valerie Strauss in the Washington Post. But having a bachelor’s degree has become a prerequisite for the success of presidential candidates, and as a result, every president since Harry Truman has graduated from college with at least a bachelor’s degree. Institutional learning versus self-education is no longer the issue. Instead politicians have refocused their efforts on debating what colleges should teach and how they should be funded.

“Why should we subsidize intellectual curiosity?” Ronald Reagan asked in a 1980 campaign speech. And so began the federal push toward education that would first and foremost produce employees. The “cup of knowledge” has become a medicinal cure-all for potential unemployment.

President Barack Obama argued for the practicality of degrees during his post State of the Union tour in 2014.

“Folks can make a lot more potentially with skilled manufacturing or the trades than they might with an art history degree,” he said. “I love art history. I don’t want to get a bunch of emails from everybody. I’m just saying, you can make a really good living and have a great career…as long as you get the skills and training that you need.”

Many politicians seem to agree with this sentiment. In a South Carolina town hall meeting, Jeb Bush said universities should guide students toward majors that result in lucrative careers and in the process lost the vote of psych majors everywhere.

“Universities ought to have skin in the game,” he said. “When a student shows up, they ought to say ‘Hey, that psych major deal, that philosophy major thing, that’s great, it’s important to have liberal arts … but realize, you’re going to be working at Chick-fil-A.’”

Bernie Sanders made headlines after introducing a bill that would make tuition free at public four-year colleges, a move that he believes will make a stronger, more competitive workforce. “In a global economy, when our young people are competing with workers from around the world, we have got to have the best educated workforce possible,” he said in a statement about the bill. “That means that we have got to make college affordable.” Sanders’s initiative, however, is not without its problems. According to U.S. News & World Report, the idea would cost “$70 billion per year” and “much of that money would provide a free education to students whose families can already afford it.”

Though politicians disagree over how college should be funded, at the heart of most of their education policies is an aim to produce an individual shaped for the job market. Consequently, most schools have been leaning away from the liberal arts. Stony Brook Professor of Economics Michael Zweig explains the utilization of education for job creation as a matter of “increasing inequality” in American society. “You won’t find pressure to do away with the humanities and social sciences at Harvard or Princeton,” he explains. “Schools that the elites send their children to are encouraged to give their students a very broad understanding of history and culture and social sciences.”

The children of elites are given this breadth of view of citizenship in anticipation of them one day becoming the “visionaries of citizens” and taking over the running of society. “The rest of the people are just supposed to work and not think about things too deeply and understand things too carefully,” Zweig says. “If ordinary people have a sense of history and civics and social history and culture and so on, they are more likely to challenge what the elites are doing.”

Comments are closed.