Graphic by Naomi Idehen.

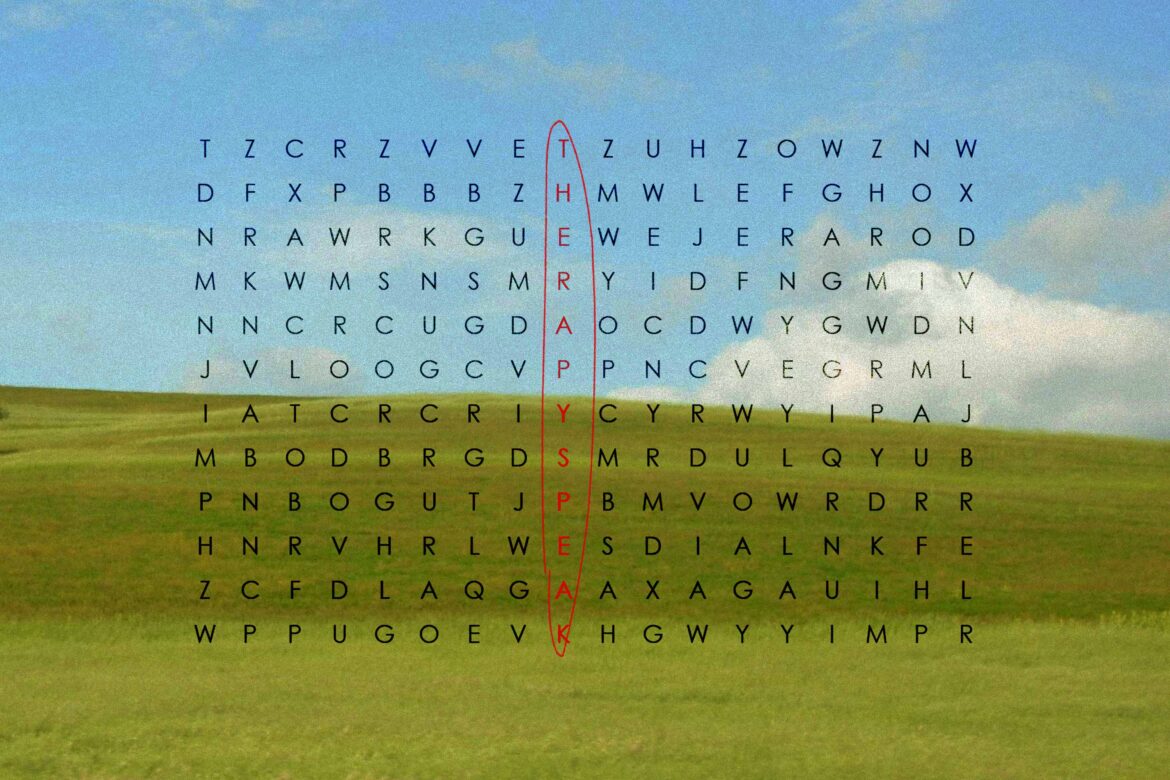

Help! I just dropped all of my toxic friends, and my narcissistic boyfriend is gaslighting me. He doesn’t understand that I have an anxious attachment style, and that I need him to follow the boundaries I’ve set because I’m so OCD. Am I practicing self-care correctly, or am I just a victim of therapy-speak?

Mental health advocacy is booming online. Licensed therapists and psychologists are growing roots outside of their brick-and-mortar offices and into the digital world as TikTok therapists provide therapeutic advice to their followers. But, in the age of misinformation, what happens when psychological jargon is misused? What impact does this have on interpersonal relationships?

There is a term for this improper use of therapeutic language — coined as therapy-speak. The phenomenon occurs when prescriptive language, which describes behaviors or psychological conditions, is used improperly outside of therapy. The expansion of mental health advocacy has allowed people to more accurately describe their feelings, better communicate with those around them and ultimately find the psychological support that they need. However, as a consequence of this expansion, more people have engaged in therapy-speak, which can open up a potentially destructive can of worms. Misunderstanding, and therefore misusing, this language can destroy relationships that could have been salvaged.

“Therapy-speak is the use of clinical and psychological language in regular, day-to-day conversations, often outside of the context within which those words were meant to be used,” Israa Nasir, 36, says. Nasir is a mental health professional, author and speaker residing in New York City who has amassed over 35,000 followers on TikTok. “An example of therapy-speak is when somebody might accuse their partner of gaslighting them, which is a very serious, emotionally abusive dynamic, when in fact, their partner was lying to them. So therapy-speak sometimes is weaponized, and intentionally or unintentionally.”

Christine Johnson, a 31-year-old therapist based in New Orleans, Louisiana, breaks down the larger notion of therapy-speak into two components. “One is the folding in of words into our general vernacular like ‘gaslighting’ or ‘narcissist’ that originated from the world of psychological sciences,” Johnson says. “The other refers to a specific tone that relies on flowery language to muddy the waters of what someone is actually saying, often in an impersonal way.”

The terms and concepts associated with therapy-speak often require their users to fully comprehend them, and use them with careful consideration, to avoid sounding like a sanitized, cold and disconnected HR email. Self-help books and online mental health advocates can only provide a framework for handling situations that arise in personal relationships. Regurgitating prescriptive language without the key ingredients — human compassion and intellect — can lead to an unfortunate collapse of those relationships.

What does weaponized therapy-speak actually look like? In April, an article on Bustle — “Is Therapy-Speak Making Us Selfish?” — examined some real-world examples of its destructiveness. In the article, a 24-year-old girl named Anna discusses how her lifelong friend abruptly ended their friendship over text.

“I’m in a place where I’m trying to honor my needs and act in alignment with what feels right within the scope of my life, and I’m afraid our friendship doesn’t seem to fit in that framework,” the friend wrote. By using one-sided, vague language, Anna’s former friend left her in a position that closed the conversation from further discussion.

A more satirical example comes from Sabrina Brier, a comedian and TikTok public figure. In a skit, Brier acts as a friend who uses therapy-speak. When asked by the person behind the camera if she will attend a housewarming party the coming weekend, Brier responds in a satirical, dramatic example of how therapy-speak may feel for the person on the receiving end.

“To be radically honest, upon further reflection, it has come to my attention that I’m no longer able to spend time with your friend group, because I find them to be insufferable and, quite frankly, toxic,” Brier replies in an exaggerated, matter-of-fact tone. “In order for us to spend more time together, it’s going to have to be one-on-one outside of them.”

“Therapy speak is the death of proper communication,” reads a comment on Brier’s video. Other comments claim that she sounds like a robot.

Therapy-speak has been criticized for encouraging people to place their wants and needs over those of others. In actuality, relationships require much more tenderness than this black-and-white thinking. Therapeutic concepts like self-care and boundary setting are important for maintaining mental health, personal growth and healthy relationships, but real-life situations are far more nuanced. Relationships sometimes require sacrificing one’s own needs and wants when the other person’s are more serious or substantial.

Self-care and mindfulness can provide numerous benefits — higher-quality sleep, boosted self-confidence, improved focus, stronger immune system and more stability when managing stressors. However, therapy-speak, and even self-care affirmations, can lead users down a dark rabbit hole. While constantly building up self-importance, someone may also be — inadvertently or not — strengthening feelings of selfishness under the guise that the self is always the priority.

Nasir contends that while therapy-speak has helped expand emotional vocabulary, it has also harmed mutuality in relationships. “Mutuality is this concept of there being an ‘other’ in a relationship, so we grow in relation to others,” she explains. “The biggest task of a therapist is to help people see that, and help negotiate these things within healthy relationships. But this proliferation of social media and therapy-speak has incorrectly and erroneously taught us that mutuality doesn’t exist.”

Dr. Raquel Martin, a licensed clinical psychologist and professor based in Nashville, Tennessee, posted a video to her TikTok account that explains the fine, but crucial difference between a “rule” and a “boundary” in personal relationships. “A boundary guides your behavior,” Martin says. “A rule guides someone else’s behavior.” She uses an example of two people engaging in a conversation, and one person raises their voice at the other. Martin says that telling the person to stop raising their voice would be considered a rule.

“A boundary would be more like, ‘When you raise your voice at me, I will not be engaging in that conversation,’” Martin says in the video. “He can keep on yelling, you’re not telling him not to yell. You’re not controlling his behavior. You’re saying what you are going to do in response to his behavior.”

A public example of this weaponized misunderstanding of boundaries came from actor Jonah Hill in July, when his ex-girlfriend, Sarah Brady, posted screenshots of their text messages to her Instagram story. In the messages, Hill demanded that Brady conform to the “boundaries” he set for their relationship. Among other things, Hill insisted that Brady — who is a surfer — needs to stop posting photos of herself in a bathing suit, and that she must not surf with men.

“He had a very strong preference for the way his girlfriend dressed,” Nasir says, in response to the Jonah Hill controversy. “But he used the term ‘boundary’ to communicate that. Boundaries are not meant to police other people’s behavior. People don’t understand that, and they kind of present their own preferences, or their own desires, or their own likes, or you know — what they expect out of the other person — and label that as a boundary.”

Why has the information age brought on this pervasive misunderstanding of therapeutic language? A possible explanation could be that the internet and social media made this language hugely accessible. People who cannot afford therapy can now do their own research on mental health. Online resources — including a scroll through TikTok — have opened this once-closed door.

“I think that society has latched onto therapy-speak in this exaggerated way because there was a huge gap in our emotional vocabulary at a societal level, and also at an individual level,” Nasir explains. “So for a very, very long time, these concepts that people really feel — people do feel a lack of boundaries, people do feel like someone is overstepping, or people do feel like someone is emotionally abusing them — they don’t really have the language for it. For many, many years, this was all gate kept behind the doors of therapy. And if you couldn’t afford it, you didn’t know it.”

People are hungry for more precise language to accurately describe their emotions or circumstances. This blending of diagnostic and therapeutic language into the vernacular allows for people to place labels on other people — or on their own feelings — as a form of catharsis, even if those labels are inaccurate. “In a world where our social and digital communication is shortening into smaller and smaller soundbites, it becomes important to find communication shorthands,” Johnson says. “Labeling someone else as a narcissist, for example, creates a communication shorthand that immediately implies a level of severity that a description of traits and behaviors might not capture as easily.”

Amanda Stern, author of Little Panic and writer of the How to Live newsletter, was in therapy for 23 years. “I can’t think of one time that my very excellent therapist ever used any of these words or expressions,” she says. “These terms help us locate the general area of difficulty. It gives us a name or a phrase for the entire sentence that we lack. This word, this phrase, is a great place to start. But people don’t start there. They finish there.”

The existence of therapy-speak is an indicator that our society is moving in a direction that is far more conscious of mental health than ever before. Stern interprets the usage of therapy-speak as a signal: the user has either just started going to therapy, or they have just begun researching mental health conditions or self-care.

“It’s a double-edged sword,” Stern says.

Stern’s 2018 memoir, Little Panic, is a reflection on growing up with an undiagnosed panic disorder. “After I published Little Panic … I noticed how many people would conflate having anxiety with having a panic disorder,” she says. “People have this need to sort of heighten or embellish or exaggerate their struggles in order to be taken seriously, or in order to be heard. But that actually backfires.”

Incorrectly self-diagnosing a mental health condition or falling victim to misusing a therapeutic buzzword creates a wall between a person and the personal or relational growth that they may be craving. While words like “gaslighting,” “trauma” or “narcissist” are not always used incorrectly, therapy-speak is a signifier that someone needs to dig deeper, rather than block off further exploration with one word.

“If you’re overlooking the actual tools needed in which to access your emotions and articulate them, and you’re actually bypassing them, and in place of all that work, you’re just tagging things with a word to signify a larger issue, you’re not creating a deep and meaningful relationship,” Stern says. “You’re just creating a show of being very well read on the internet.”

How can we avoid this harmful misuse of therapeutic language? Therapy-speak is an indicator that there may be more complex, nuanced emotions hiding below the surface of a buzzword that is being used. Instead of viewing that connection — with a particular phrase or term that is floating around the social mediascape — as an immediate fix, view it as a means to beginning a self-discovery journey.

“I’d love to see a greater respect for the ways therapy language can help a person define their own experience and a greater caution for the harm it can cause when used to define someone else,” Johnson says, while weighing the benefits and drawbacks of therapy-speak. The key to using this language accurately might lie within mindfulness, conversation and careful consumption of information online.

“We need to become conscious consumers,” Nasir says. “We need to look at the credentials, we need to look at their training, we need to look at their overall messaging. More than anything … If you’re struggling, try to seek one-on-one care, because what’s happened is a lot of us think that this access to information is treatment itself, but it’s not.”

Because individualized care is sometimes inaccessible due to cost, Nasir encourages people who are struggling to find affordable therapy to explore every option. She suggests checking to see if there is a community clinic in your area, looking into group therapy — as it is usually cheaper than one-on-one — and asking therapists for a sliding payment scale based on income. “There are a lot of free community services provided around mental health care,” Nasir says. “It’s still not as good as one-on-one care, but it’s still better than just passively consuming information on the internet.”

Aside from taking mental health concerns directly to a therapist, therapy-speak can be used as a starting point for individual growth. “Everyone should say to themselves, ‘Say more,’” Stern says — her rule of thumb for engaging with therapy-speak. “Say more, get your own words. Trace it back to the root.”

While a singular term or phrase may feel fully-encapsulating of a person, emotion or relationship, that prescriptive language may not perfectly fit the bill. Before hitting send on that break-up text to a friend who violated a set “boundary” at brunch, or whispering about a partner’s “narcissistic” tendencies behind closed doors, think twice. What colorful, multi-dimensional emotions are buried beneath that buzzword? Therapy-speak expands emotional literacy — it can help people identify serious disorders or legitimately dangerous relationships. But this language may require a warning label: use with well-educated caution, or else risk collateral damage to healthy communication and interpersonal relationships.

Comments are closed.