Graphic by Sabrina Lee

My name is Arun Nair. I am a science editor at The Stony Brook Press and a recent graduate of Stony Brook, where I studied neuroscience and creative writing. I am also a severely disabled young man.

In 2009, I came back from a two-year tour in Iraq with no visible injuries. I became disabled after being hit by a car on Memorial Day weekend of 2012. I was initially in a coma for a month, and moved from one hospital to another and finally back to my parents’ house on the border of Queens and Nassau County around Veterans Day of that year. While I was in that coma, I had a stroke on the left side of my brain, and when I woke up, I was paralyzed on the right side. After months of physical therapy, I received deep brain stimulation (DBS) surgery in 2014 because my relatively young age and good health made me a good candidate for this invasive procedure. It had a profound impact on my life — after intense physical therapy, DBS and some additional treatments, I regained enough movement and control to return to school in the summer of 2017.

This summer, I discovered that two physicians — one pediatric neurologist and one neurosurgeon — were living just upstairs from my aunt in Brooklyn. Both Dr. Lekshmi Peringaserry Sateesh and Dr. Vinayak Narayan are from the same part of India as my own family — Kerala — and both doctors also have experience with DBS.

The three of us shared breakfast and coffee at my aunt’s dining room table while speaking about this procedure and the field of neurology as a whole.

I know they do deep brain stimulation, the surgery that I got, at NYU Langone. Is that where you work, or do you work somewhere else?

Dr. Narayan: Yes, I work at NYU Langone.

Dr. Sateesh: I work at SUNY Downstate, where I am a pediatric neurology resident. I’m in my fourth year of residency. It’s a five-year program.

What got you interested in neurosurgery?

Dr. Narayan: During my time in med school, I was really fascinated by the anatomy of the brain and spinal cord. When I started seeing patients, I was interested in seeing neurological problems. At the same time, I started getting interested, watching surgeries and performing some basic small surgeries. So, combining the surgical field and neuroscience, I decided to take my career ahead with the neurosurgery specialization.

What got you interested in pediatric neurology?

Dr. Sateesh: I like children, and I like to help them. I like pediatrics. And also I like neurology. That’s why I wanted to do pediatric neurology — I like both specialties. And I cannot do both separately, so I thought I’d do neurology for kids. Neurology is a very interesting specialty. It’s kind of a puzzle. I always liked to solve puzzles.

What roles do neurology and neurosurgery play in human lives?

Dr. Narayan: The brain is the most vital organ of the human body. There are many kinds of diseases that can affect the brain. So, the types of illness which can be treated by surgery are taken care of by a group of doctors called neurosurgeons, and certain diseases that can be treated with medicines are taken care of by the neurologist, or the neurophysician. So, that’s where both jobs are coming into play in the treatment of neurological diseases.

Dr. Sateesh: The brain [has] supreme control of all other organs; it frames the topmost part of your body — it even controls emotions or feelings. People think emotions come from the heart, but they don’t. They actually come from a particular part of the brain. And that’s why it’s very important in our lives.

In basic terms, what is deep brain stimulation? How is it performed?

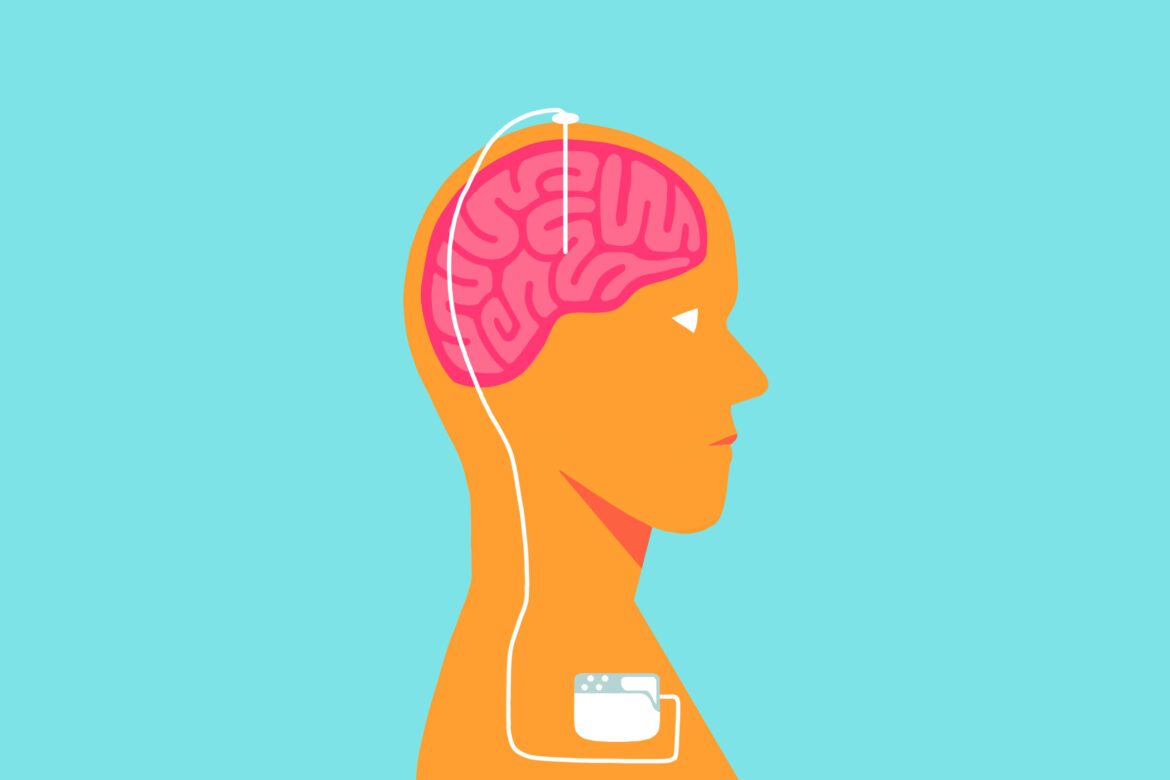

Dr. Narayan: Deep brain stimulation is a very complex kind of neurosurgery in which, as the name indicates, we are stimulating very specific deep tissue in the brain by implanting a pacemaker inside of the brain. This pacemaker within the brain is connected externally to a battery, and this battery will constantly deliver some kind of electricity to those pacemaker electrodes and stimulate the brain structures.

How was the technique developed?

Dr. Narayan: Deep brain stimulation was developed many years ago and the concept considered the head in a stereotactic space, and based on that stereotactic dimension, people started thinking, “We can focus on one particular point in a coordinate system.” So, based on that, we can precisely target a certain area or certain nucleus within the brain, and the stimulation of that structure can lead to remarkable benefits for the patient. A man named Dr. Lars Leksell pioneered this system and developed it. … Nobody was aware of such a treatment. Many changes and modifications have happened to the system. Nowadays, we can provide really advanced treatment with DBS. It’s very, very beneficial — amazing, actually.

What are its strengths and limitations?

Dr. Narayan: Deep brain stimulation can be used for Parkinson’s disease patients who are having a very bad tremor or rigidity, really classical forms of the disease. It can be done for essential tremors, which are really severe tremors that affect a person’s quality of life. DBS is also used for the treatment of certain kinds of epilepsy or seizure disorders. Nowadays, it is also used for psychiatric disorders like depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, addictions and other issues.

The limitations are that we have to do a lot of testing prior to the procedure. And only after doing all these tests can we decide if candidacy for this procedure is possible — only a few people are good candidates. The second thing is the patients should be well-motivated, and there should be strong support for these patients. Even after the procedure, they will need a lot of help in terms of hospitals, treatment and everything. So, there should be a strong support group for these patients, and they should be responding to certain types of medications or willing to take some medications even after procedures. So those are the limitations that make many patients not good candidates for DBS.

I had a stroke and got DBS as a result. What is done for people who have had a stroke to bring back normal function?

Dr. Narayan: If a person has had a stroke, to bring back normal functioning, the most important thing needed is courage and a strong mind to come back to his life. That’s the most important thing they may need. Provided they’re supported with other kinds of continuing medical treatments, like good rehab treatment, like speech therapy if they’re having speech issues and physical rehab treatment — all those things are really important. At the same time, preventing another stroke by treating the risk factors is very important.

If you find a fetus has a neurological issue, what can you do for it or for the mother?

Dr. Narayan: If a fetus has a problem, it can be detected to some extent by doing a blood test on the mother. We may be able to detect it in the initial months of pregnancy. For a few of the problems we can predict in utero, neurosurgical treatment options are available. However, many times these problems are pretty severe. Preventing those problems is something we can [try to] do. One thing we can do is counsel mothers to take the needed medications, like certain kinds of vitamins or iron tablets. But certain kinds of genetic problems, of course, we cannot avoid and we have to accept the fact of the poor prognosis.

Dr. Sateesh: There are certain genetic conditions that we can pick up very early during first-trimester and second-trimester blood screenings. For example, there are diseases with a very poor prognosis like spinal muscular atrophy, which can be picked up prenatally. Treatment is limited, but there are advanced treatments we can do: in-utero procedures and in-utero intrathecal therapy. Again, the prognosis is poor either way.

What is the future of deep brain stimulation? Are there other techniques in development that could supplement or improve it?

Dr. Narayan: I think there’ll be robust applications for deep brain stimulation. Primarily, we are using it nowadays for tremors, for Parkinson’s disease and for epilepsy, but the future may be more focused on psychiatric disorders like depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder and addiction in patients which are refractory to routine medications. That will be a great platform for DBS to show its power. The advanced technologies we have now have some very, very safe deep brain stimulation treatments, like tractography. … So, in the development of those things, DBS is going to be very safe and very effective for the management and treatment of many of these neurosurgical problems in the future of care.

Tell me about some challenging or unique experiences you’ve had.

Dr. Narayan: One unique experience I had was when I was in Ohio, during my fellowship in stereotactic and functional neurosurgery. I saw a patient who had a very debilitating tremor, which he had been suffering with for more than 40 years. He was 75-plus in age, a gentleman who was not able to do anything because of his tremor — he was not able to have food by himself; he was not able to hold a spoon by himself; not able to drink water by himself. So he came to a treatment called MRI-guided focused ultrasound ablation treatment. This is a surgical procedure and it takes around two to three hours.

We finished [his] procedure in a three-hour time span. And once the procedure was completed, he had almost complete improvement of his tremor, and now he’s able to drink by himself, to have food by himself. His life has completely transitioned, almost like a 180-degree turn in treatment. At the end of those two, three hours, he was feeling like magic and [it was] one of the most important things that happened in his life. So that was a very unique experience to me, and it’s the kind of patient happiness that, in our field, is very, very rewarding.

Dr. Sateesh: During my residency days, I had some challenging cases. One of the cases was a newborn baby, born to a normal mom, normal family, no other risk factors. But the baby had significant abnormalities from head to toe, with significant facial dysmorphism and limb abnormalities. It wasn’t responding very well to any kind of treatment and needed respiratory support among other kinds.

It was very challenging to find out what the baby had; it was very interesting as well as challenging. So we did imaging, we did the EEG, the EMG — all kinds of neurological investigations. Finally, we got a positive genetic testing, which revealed a very, very rare genetic abnormality with the baby. I think it was the second case of its kind in the U.S., so we couldn’t even find much maintenance around this genetic abnormality. But the problem was — even though eventually we were able to find out the diagnosis — we didn’t have much treatment for the disease, so we were unable to help the baby in any way, other than supportive measures. So that is a sad part for those diseases. But the good thing is we were able to at least find out what was the cause.

Comments are closed.