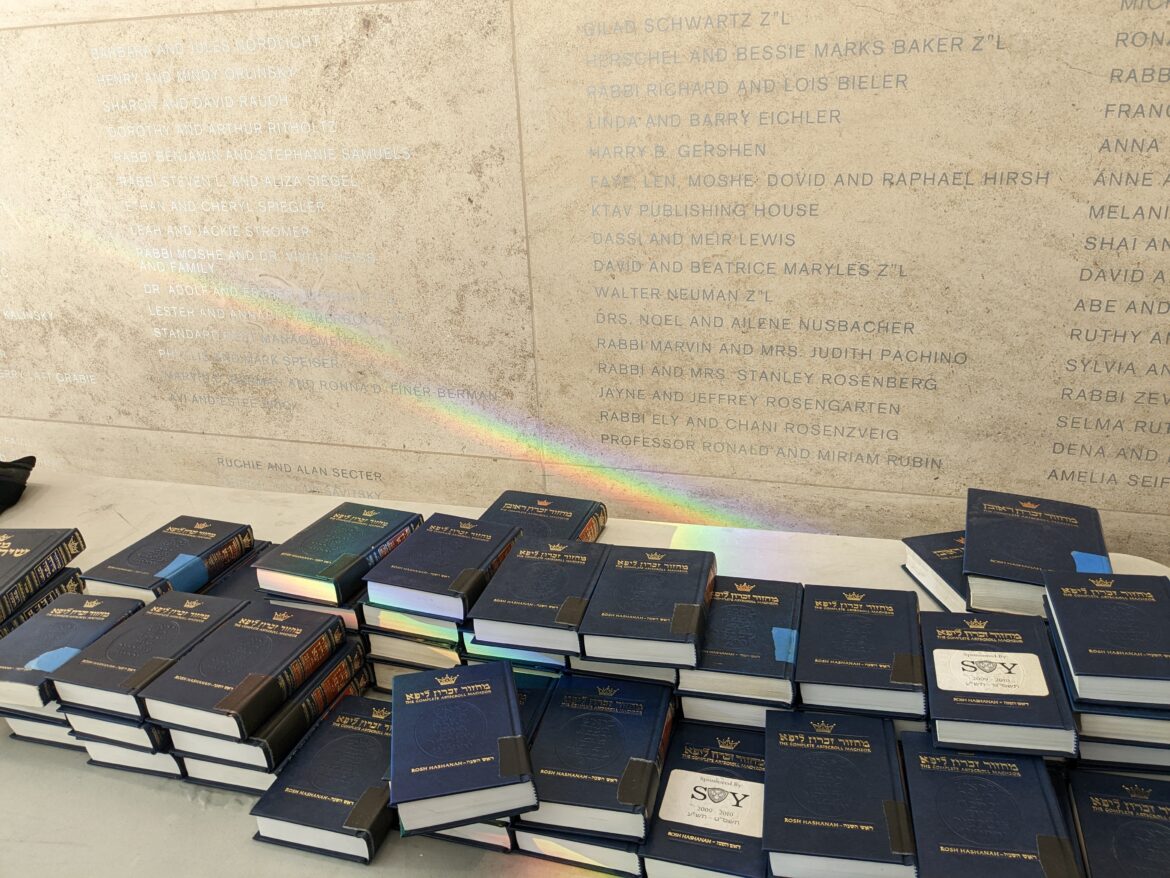

Yeshiva University’s Wilf Campus is a lot smaller and quieter than our own at Stony Brook University. Yeshiva University (YU) is a private Orthodox Jewish university with four campuses in New York City — the Wilf Campus is located in Washington Heights. During Rosh Hashanah, it was especially serene. Women in muted floral skirts and dresses pushed strollers, walking with older children at their side. Well-dressed Orthodox men filed into the Glueck Center Beis Medrash, grabbing a copy of the machzor from the foyer to celebrate the Jewish New Year on their way in.

An angular rainbow filtered through the window onto a table where the holy prayer books were neatly stacked. I looked through a glass door with a white privacy shutter, caught a glimpse of the men again and suddenly felt like an intruder. I headed out.

The rainbow cast across the machzorim — that’s what this story is about. On Sept. 16, 2022, Yeshiva University banned the only student-run LGBT club on its campus. This is not their first fight. YU’s queer students have been struggling for an officially sanctioned place to belong for over a decade.

On the side of a building by a major thoroughfare at YU, “Core Torah Values” are emblazoned: infinite human worth, compassion, life, truth and redemption. The colorful banners remind me of pride flags. I wonder whether the university has lived up to what it says it believes in.

INFINITE HUMAN WORTH

There are sizable groups of Orthodox Jews who not only tolerate gay members, but embrace them wholeheartedly. Eshel and Jewish Queer Youth are two organizations fulfilling this role. Their opponents argue that halakha, Jewish law, prohibits same-sex relations. Although religious grounds for homophobia have long preceded the events at YU, the recent history is worth mentioning. It starts with the administration’s response to the Tolerance Club in 2009.

The Tolerance Club was a small group devoted to altruism but unsure of its ultimate goals. It put up posters on campus that asked students to be kind — Tolerance Club members called it the Nice Campaign. They published a newsletter arguing that “every person, within YU and without, deserves to be treated with dignity and respect.” Only 15 students attended the first meeting.

Later that year, the club invited queer students and alumni to speak about their lives. In the Weissburg Commons — a lecture and event hall at YU — 700 students curious about gay life in a Modern Orthodox world crowded around one another to listen.

COMPASSION

The speakers took pains not to speak to the halakhic implications of queer lifestyles. A YU administrator moderated the discussion. It seemed that the Tolerance Club and the university’s School of Social Work, which co-sponsored the event, had struck the impossible balance needed to humanize gay suffering without overstepping into scriptural debate.

It didn’t work. A firestorm of bad press immediately followed and Yeshiva’s president professed a sort of pity for those who spoke — and for people like them: “those struggling with this issue require due sensitivity, although such sensitivity cannot be allowed to erode the Torah’s unequivocal condemnation of such activity.”

In another statement, five of the school’s deans went further: “Homosexual activity constitutes an abomination … As such, publicizing or seeking legitimization even for the homosexual orientation one feels runs contrary to Torah.”

The Tolerance Club disbanded.

TRUTH

After the Tolerance Club, gay students at Yeshiva wouldn’t be in the national spotlight for another 10 years. Life went on, though — if you dig, you’ll find a queer Facebook group dating back to 2011, blogs describing the fallout of the Weissburg panel and a few other signs of LGBT student life. 2017’s Diversity Club sought to “celebrate what makes us unique, and remind ourselves of everything that connects us.”

The current generation of gay students at Yeshiva, YU Pride, did not mobilize a Nice Campaign — it sued the university for equal recognition alongside other student organizations. YU Pride believes that the university is violating the New York City Human Rights Law. By refusing to formally approve YU Pride, the argument goes, the administration is treating queer students as second-class citizens. YU Pride won its first lawsuit.

Yeshiva University did not concede. The administration appealed the case to the U.S. Supreme Court, arguing that to compel the university to accept YU Pride constituted an “unprecedented intrusion into Yeshiva’s church autonomy.” In seeking parity over tolerance, Yeshiva administrators believe YU Pride has overstepped.

The Supreme Court ruled that Yeshiva University had not exhausted its appeals in New York, and returned the case to the state. YU exercised its vaunted autonomy. University administrators banned every student club on campus. A de facto moratorium on all club activity created social pressure among students that made it impossible for YU Pride to keep pushing for an official seal of approval without alienating its peers. Exercising grace unseen within their own university administration, the members of YU Pride decided to pause their fight until all administration appeals are exhausted in the courts.

Yeshiva University, feeling the burn of the national spotlight, has created its own LGBT club that is not run by students: Kol Yisrael Areivim. The Hebrew translates to, roughly, “All Jews are responsible for one another.” The effectively faux club exists only in press releases, statements and a word that kept appearing in my search: “framework.” “Skeleton” feels more appropriate.

LIFE

Orthodox Jewish communities can be tightly knit, which makes them seem opaque to outsiders like college students at non-Jewish universities. Stony Brook junior Leah Schwarz, with a pen in her hand outside the Melville Library Starbucks, outlined the three largest denominations of Judaism. Schwarz is both Jewish and queer — her aunt attended Yeshiva.

“It’s interesting to me, from an anthropological perspective, how communities change over time,” Schwarz said, describing the three main arteries of modern Judaism: Orthodox, Conservative and Reform.

“With queer Jews, the reformists are totally fine with that. There are certain topics being contested in the larger Jewish community. Another thing debated a lot is female Rabbis.”

Yeshiva University claims to be queer-affirming. However, this affirmation comes with a heavy asterisk: hate the sin and not the sinner. That asterisk is revealed in the university’s stated priority: helping gay students navigate “the formidable challenges that they face in living a fully committed, uncompromisingly authentic halakhic life within Orthodox communities,” implying that commitment (to core Torah values) and authenticity (being gay) are disharmonious co-obstacles.

Schwarz observed that, to her, many of the students at YU are acting as bystanders to the surrounding power struggle. Schwarz framed many students’ passive rationale as such: “The university didn’t do anything rude to me personally — I’m still allowed at events.”

REDEMPTION

Back at Stony Brook, Jessica Lemons, the executive director of Stony Brook Hillel, explained the difference in vision between Yeshiva and SBU. Besides the obvious distinction of Orthodox Jewish versus public secular, there are subtler ones. Hillel’s stated mission is to become “a home for Jewish students to explore their relationship with Judaism, Israel and each other.” “Hillel is a pluralistic organization,” Lemons said, “which means that we do not affiliate with any one denomination of Judaism like Orthodox, Conservative or Reform. We have students of all observance levels. Hillel aims to be a very LGBTQ-affirming space.”

How does Hillel do that?

“I think there are a lot of layers to it,” Lemons said. “More openly, making sure that we have appropriate signage.” More deeply, Lemons said:

“I believe that the tenants of Judaism and what it means to be Jewish is to be welcoming and inclusive of people so that they feel safe to be Jewish in your space. So if we are going to turn away Jews because of how they love and how they show up in the world, that’s just not the Judaism that I want to provide for our students.”

Lemons’ advice for the students at Yeshiva is to take care of themselves.

“You as a person are priority number one, and if that means continuing to rage against the machine … or removing yourself from that situation, … both of those things are valid. Don’t let it destroy your relationship with Judaism.”

For now, Yeshiva University’s tactic of collective club canceling and the resultant compromise has held. But on Dec. 15, 2022, the university lost an appeal in a mid-level court. This means there are two arenas left for the final word on whether Yeshiva must officially recognize YU Pride: the New York Court of Appeals and the Supreme Court of the United States. The fate of those living in the vicinity of a rainbow cast delicately across the machzor in the first days of a Jewish New Year remains to be seen.

Comments are closed.