We’re shucked, if Annemarie Waugh has anything to say about it.

In the Lawrence Alloway Gallery on the bottom floor of Melville Library, the walls are bedecked with flora and paint, and piles of seeming garbage lay in corners and on a pedestal in the center of the room.

Waugh, a Stony Brook University art professor, is the mind behind “#Shucked.” In combinations of organic and inorganic pieces — rocks, shells and pine needles mixed with bottle caps, sand and duct tape — Waugh expresses human influence on nature.

“This is just an artist’s impression of contemporary life,” Waugh said. “And it’s pretty sad.”

Sad indeed — Long Island is no stranger to man-made ecological disasters. According to the United Nations, 8 million tons of plastic get dumped in the ocean every year. Over 90% of adult Peconic Bay scallops, a Long Island staple, have died this season from what was likely a protozoan parasite. New York State’s bee population has been declining. And urban development has chipped away at most of the island’s wilderness.

“It’s hard to find joy in this subject, but I seem to be drawn to it,” Waugh said. “I try to just work from what I feel.”

Waugh has lived in Setauket with her husband and son for 14 years. She’s had art exhibitions in Islip, Stony Brook and Patchogue, and gardens religiously. But Long Island, and the species that call it home, is changing all around her.

“Rising ocean temperatures, strange climate patterns,” Waugh said. “Yeah, I’m reacting to that.”

So Waugh turned to art to express her sadness. “Vanishing,” an ongoing art project, depicts various Long Island species — like eelgrass beds, clams and bees — slowly fading through sets of identical sketches. A 2019 piece called “What the Monarch told me” encouraged participants to take home poems with packets of milkweed seeds — from the plant monarch butterflies rely on for food, reproduction and the source of their poison. Waugh started brainstorming and creating “#Shucked” last September.

The environment has always been a theme in art for creators to flex their creativity, and explore the line between craft and activism. New York artist Agnes Denes planted two acres of wheat in lower Manhattan two blocks from Wall Street in 1982. Mel Chin, a Chinese artist and sculptor, took over Times Square in the summer of 2018 with “Wake,” a giant sculpture of a ship crossed with a whale’s rib cage, and “Unmoored,” a virtual reality app that depicts the city submerged in a post-global warming future.

This isn’t limited to just artwork either — musicians express their perceived helplessness through song. British rock band Foals’ most recent pair of albums, Everything Not Saved Will Be Lost — Part 1 and Part 2, were born of the anxiety they feel as they watch world leaders do nothing about climate change. The album and song artwork for Part 1 is part of an ongoing series called “Sublimis” by artist Vicente Munoz — he highlights vegetation in aerial urban photographs through an infrared lens, bleaching the buildings and turning the plants blood-red, in order to “explore the inevitable struggle of man against nature—his desire to control and tame it through the constant thrust of urbanization.”

Part 2 drops more anvils with the music video for “Like Lightning,” where a yeti-like creature named George inspires humanity to give up meat, plant trees and save the planet — all while a rock anthem admonishes listeners: “You just think about yourself/You should get some help/Be somebody new.”

It’s one thing for a scientist to issue a warning in a journal, or for a tree-hugger to write a song for his fellow tree-huggers to sing along to at festivals. It’s another thing entirely to try to push climate awareness — that latent frustration and doom that percolates within all of us — into the artistic mainstream. It requires deep, critical thought about messaging, communication and audiences. How exactly does an artist channel their inner anger into something not only expressive, but communicative? For many, it requires packaging their environmentalism in good art. A tuneful song like King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard’s “Plastic Boogie” doesn’t exist just to be a climate-woke admonition of the human race — it’s also just a straight-up bop.

Further towards the accusatory, artists don’t hesitate to name names. Parquet Courts’ “Before The Water Gets Too High” addresses climate change as it relates to class, government and systems that oppose effective change. Tonally, this is more extreme than King Gizzard, but from a theoretical perspective, it carries more nuance within its 4-minute runtime.

Writing a good piece of climate art also requires that the artist avoid two cliched extremes: the finger-wagging trap of a protest song, and the infantile palatability of a song that abdicates its responsibility to even address the subject.

The former extreme contains the kind of alarmism often dismissed as too preachy, no matter how right it may be. Screaming at a crowd of people to radically change their lifestyles is ineffective — and it generally makes for bad art. Without some artistic perspective beyond a binary earth-good, us-bad narrative, this kind of activism falls on deaf ears.

At the latter end of the spectrum is the kind of art that hinges its appeal on its supposed, implied relationship with climate awareness. Take a song like Lil Dicky’s “Earth,” a litany of animal names and superstar features that culminates in a flaccid “we love the Earth, it is our planet.” Never speaking directly about climate change, the song flouts its responsibility in an increasingly alarming situation — resorting instead to the kind of toddler-esque identification we last heard in grade school. This ultra-palatable type of climate art is just as bad as thinly veiled guilting. It doesn’t help that the tune also sucks.

Disaster movies about man’s destruction of nature — and even of nature lashing back — range from 1973’s Soylent Green to 2008’s The Happening to 2014’s Snowpiercer. James Patterson’s Zoo introduces radio wave- and plastic-modified pheromones that force animals to attack humans. Hollywood tends to go big, bold and violent — massive floods, vengeful wildlife and cities burning on an orange horizon.

But what kind of impact does media like this make? Well, it depends. In an Oct. 2017 New York Times article, University of Michigan environmental professor Andrew Hoffman said, “Typically, if you really want to mobilize people to act, you don’t scare the hell out of them and convince them that the situation is hopeless.” A small 2019 study of an art exhibition in Paris suggested media that has a hopeful message, instead of one that terrifies the audience, tends to leave a better impression.

This is something Waugh kept in mind. “I’m just trying to engage the topic with people because there’s a fine line,” she said. “You can be really preachy. So I kind of use humor and color.”

Waugh’s materials are often things she finds and collects. She dipped clusters of pine needles from her garden’s pitch pine tree in plastic, spray-painted the tips yellow, then stuck them on the wall in the shape of a frowning emoji. The drooping needles cast sharp shadows, and will turn white as the boughs die over the course of the exhibition.

“You can call this number to hear his story,” Waugh said, gesturing to a vinyl decal on the wall. Over the phone, a chainsaw buzz crackled.

From the middle wall hang two tall sheets of brown amate, a bark paper made by the Nahua people in Mexico since pre-colonial times. Waugh threaded strips of vinyl caution tape through the rows of holes running across the paper. “Sunset 1” and “Sunset 2,” as she calls them, represent humanity’s interference in nature.

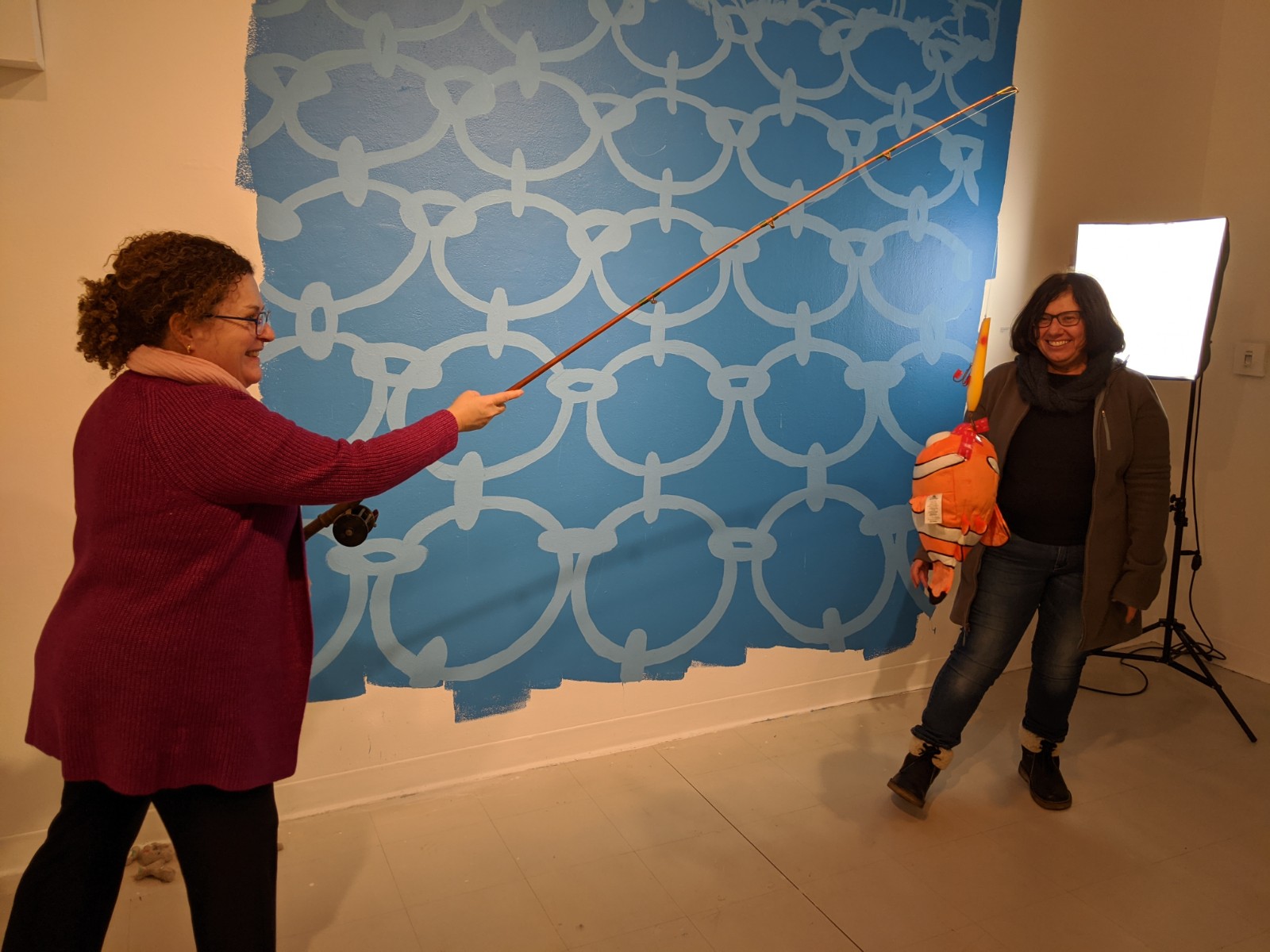

On the right wall, she painted a mural, a direct response to the dredge, titled “Me Being a Scallop: That’s What I’m Seeing.” The chain pattern of the rusty contraption was reversed and upside down, as if it were viewed through deep-sea waters. A simple shift in point of view transformed the dormant tool on the wall into an imposing cage.

In the left corner of the room, she mounted a rusty sea scallop dredge in front of a bench. A speaker hung overhead, providing a constant monologue from a fictional character named Lulu:

“I can be my true self. I’m living my best life. I’m so going shopping for the next two days straight!”

Ringing with the vocal fry of a valley girl and seemingly innocuous, the character’s voice quickly turned sinister, as a satire of consumerism became an attack on harmful scallop dredging.

“I just want them to be sheared and shucked forever!”

Comments are closed.