By Keating Zelenke and Jane Montalto. Photo by Jane Montalto.

On Friday, Feb. 10, Stony Brook University’s Mobility and Parking Services (MAPS) sent out an email addressed to the Stony Brook community, revealing their plans to implement a “campus-wide, fully paid parking model.” Within hours, the campus’s classrooms, dining halls and dorms were ablaze with discussions between students — many of them outraged — about how the proposal would affect their finances and education. Less than a week after MAPS sent out their initial email, students mobilized to protest against the proposed changes.

A single line in the email went largely unnoticed by the undergraduate student body: “The details of this tiered parking model were shared today with campus stakeholders, including representation from our various unions and student government.”

Just four hours before many undergraduates would first skim over the email from MAPS, a group of campus employees gathered at 10 a.m. in the Wang Center to hear an announcement from some administrators. A few of them had some idea of what was coming. Amy Pacholk — a surgical trauma ICU nurse at Stony Brook University Hospital and council leader of the Public Employees Federation (PEF) on campus — felt that a parking fee increase was on the horizon for her and her fellow union members.

“I literally thought they were going to ask us for a $2 to $5 increase,” she said.

Hospital employees, which constitute the majority of PEF members, already pay a little over $16 a month to park in either the parking garages or the flat lots surrounding the hospital. Under the tiered parking plan proposed by MAPS, all employee parking on the hospital campus would be considered either premium or perimeter lots.

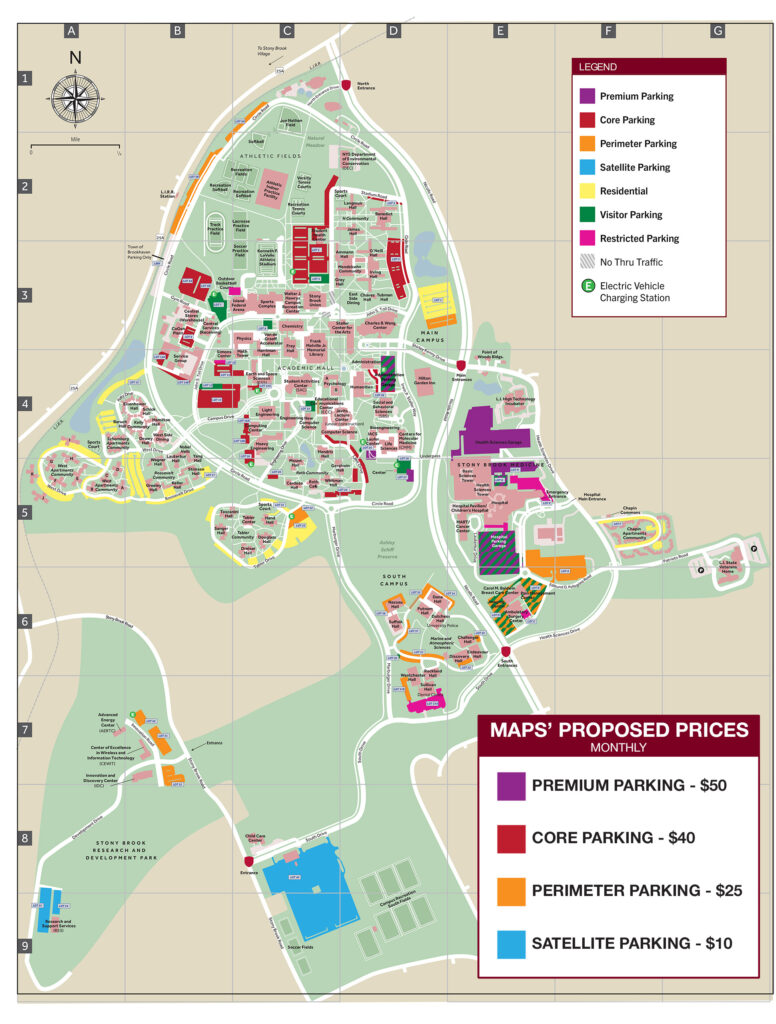

Based on information obtained by The Press outlining MAPS’ proposal to the union leaders on Feb. 10, the cost of parking in a premium lot would skyrocket to $50 a month, and to $25 a month for parking in a perimeter lot.

“The way that they’re putting it is that everybody will pay to stay,” Carlos Speight, president of Civil Service Employee Association (CSEA) Local 614, said.

“They kept saying, ‘it’s your choice,’ but it’s not your choice if you’re a single parent. It’s not your choice when you’re a student that’s working full-time and going to school.”

CSEA represents about 2,700 university employees — custodial, clerical and maintenance staff, as well as nursing assistants and licensed practical nurses. These employees now face the decision to potentially pay over three times the current price or pay $10 a month to use satellite parking — Lot 40, formerly called South P Lot — and rely on an unpredictable bus schedule that could jeopardize their work performance. In addition to premium, perimeter and satellite parking, MAPS also intends to charge $40 a month for “core” parking in the heart of West Campus. These prices are the starting point for negotiations with all the university unions and are subject to change.

It’s unclear whether the reliability of campus busing will improve as this new plan is implemented. Based on documents from MAPS, the section of their budget allocated for payroll will increase by nearly $500,000 over the next academic year. However, most of this increase will come from the transfer of some parking enforcement staff salaries from UPD to MAPS, according to Executive Director of Parking and Transportation Kendra Violet. In a presentation at an Undergraduate Student Government (USG) senate meeting on Feb. 16, Violet noted that their team of parking enforcement officers had been understaffed until this semester. Additionally, MAPS recently established new administrative positions to “oversee” operations. She did not outline plans to hire more bus drivers or extend service hours, despite their clear necessity to her proposed plan.

Speight emphasized his safety concerns for employees who work late night shifts having to take a bus in the middle of the night or early in the morning — if the buses will even be running at those times. Currently, buses from Lot 40 only run to the hospital between 7 a.m. and 11:30 p.m. For students and employees who work on Stony Brook’s main campus, they stop running even earlier, just before 11:00 p.m.

Apart from safety, Speight also noted the sheer inconvenience that parking in a lot over a mile and a half away from the center of the academic campus and the hospital main entrance poses to employees. “If you have an emergency and you have to leave, now you have to wait for a bus?”

Pacholk expressed a similar sentiment, saying that if employees can’t count on the buses to arrive at the hospital on a strict schedule, their pay period should begin the second they park their cars in the satellite lots instead of penalized for any potential lateness.

“If people have to take the bus because they can’t afford to park in the garage… that’s when their day starts — period,” she said.

Among the unions present at the Wang Center meeting was the Graduate Student Employee Union (GSEU). Unlike Pacholk from PEF, they had no idea what would be discussed.

“We asked them to send an agenda or some more information,” Doğa Öner, president of the GSEU, recalled. MAPS dismissed the GSEU’s request by explaining this would only be an informational meeting.

This dismissal was characteristic of MAPS’ presentation of this proposal to the campus community. Union leaders from the GSEU, PEF and CSEA Local 614 all expressed that they felt the MAPS administration was either disrespectful, incompetent or both, specifically referencing Kendra Violet and Lawrence Zacarese, the university’s vice president for risk management and chief security officer. Pacholk said that when she asked if the MAPS administrators understood the strain this change would impose on workers, “they literally shrugged their shoulders, like, ‘Oh, I don’t care, doesn’t matter.’”

“It was just the straight disrespect in the way we were spoken to,” Pacholk said, explaining why so many union members left that meeting in the Wang Center outraged. “[It was] like we had done something wrong. They were calling us and asking us to increase the rate, right?”

Öner pointed out that MAPS had not been following basic protocols for official negotiations, demanding to schedule their first negotiation with GSEU less than a week ahead of time. “We need at least 10 business days in advance notice,” he said. “That’s the common sense procedure for professional communications.”

For the GSEU, paying an additional fee to park is an especially critical blow. Their fight for higher wages has been accelerating for the past two years. Recently, the university administration announced that by next October, they plan to increase the current base stipend for graduate workers to $26,000. While this raise will undoubtedly make a difference in the lives of hundreds of graduate students, it’s ultimately a drop in the bucket on the way to a living wage. In Suffolk County, $26,000 a year still leaves graduate students over $4,500 below the extreme poverty line, according to the Department of Housing and Urban Development. These student employees are already struggling to afford rent, food, healthcare and other necessities; even an extra $120 a year for the lowest tier of the proposed parking plan is difficult to scrape together. For a parking spot on the “core” of campus, they’re looking at nearly $500. That kind of additional spending simply isn’t an option for most GSEU members — and a number of custodial, instructional, clerical and culinary staff.

“We’re going to be pushed to the periphery of campus, parking at the worst possible spots, making it difficult to work as we need to,” Kaya Turan, an organizer for the GSEU, said. During the meeting in the Wang Center, some union members described the potential environment this proposed plan may cultivate as a “caste system.”

“They’re offering an illusion of choice, where you can pay more money to park at better areas of campus, closer to the campus center,” Turan said. “For most of our unit, that doesn’t constitute a real choice, because they don’t have the means to be spending the extra money for parking.”

If you ask MAPS’ head administrators, their department’s financial woes go back 30 years — that is the narrative Kendra Violet and her colleagues have been presenting to various groups on campus.

MAPS is a fully self-sustained operation. They operate through an Income Fund Reimbursable (IFR) account, where their capital consists of revenue generated via parking tickets, metered parking, hospital employees’ monthly parking payments, grants and money from individual academic departments to cover the cost of parking spaces in lots currently reserved for faculty and staff. Additionally, this past academic year, MAPS implemented a premium parking plan for commuter students, which restricted free parking during regular school hours to Lot 40, on the south end of campus. To park in the commuter lots on the north side of campus — near the train station, behind Student Health Services and around the H and Mendelsohn communities, comparatively much closer to the academic mall — students were required to pay over $100 per semester. Violet later revealed that the commuter premium passes were a soft rollout for the fully paid parking model MAPS has proposed for next fall.

This came to light when Violet directly addressed the student body about MAPS’ proposed plan for the first time during the USG senate meeting on Feb. 16. The meeting was originally intended to be in the Student Activities Center (SAC), but moved less than four hours before the scheduled start time to the Alan S. deVries Center on the other side of campus. The last-minute change, once again characteristic of MAPS’ chaotic communication , was done in anticipation of a crowd of students opposing the plan.

Violet stood at a podium in front of the USG senate and executive council, and a group of 10-20 angry graduate and undergraduate students. They looked at her with harsh faces, waiting for the answers they hoped might placate their confusion and outrage. Violet seemed nervous by the end. Perhaps she was intimidated by the onslaught of questions that immediately followed her presentation — intimidated in the way only a person who makes nearly $200,000 a year can be when asking a group of people who regularly struggle to afford basic necessities for more money.

Violet underscored the fact that MAPS receives no funding directly from the university’s administration. As she and her colleagues are quick to cite, MAPS has not increased the cost of parking for students or employees over the past 30 years. Many of their parking facilities are now reaching the end of their functional life and need extensive repairs. The parking situation at the hospital, she explained, is especially dire. In the garages, sediment falls from the ceiling and damages cars. Flat lots and garages alike need their lines repainted.

Additionally, the hospital lots are facing serious capacity issues — Amy Pacholk said she was often unable to get a spot in the garages, despite paying monthly for a permit. Carlos Speight said the lots are often so full that hit-and-runs are common.

“People back up and because the parking spots are so small, they back into each other,” he said. “And nobody reports it because there’s not enough cameras.”

MAPS’ planned improvements to hospital parking — including dealing with these capacity issues and more — are projected to cost somewhere around $30 million. With that $30 million plan in mind, plus all of the proposed technology updates and necessary repairs to West Campus facilities, MAPS will be facing an $11 million deficit within three to four years if they do not adjust their business approach. This bottom line was also presented to union representatives during their meeting in the Wang Center on Feb. 10.

“We’re footing the bill for their misuse and misspendings,” Speight said.

MAPS insists in their presentations that this proposed plan would bring Stony Brook in line with similar institutions. However, the parking plans at other large SUNYs, like UBuffalo and UAlbany, do not look like what is being proposed for this campus. Undergraduate students at UBuffalo pay no additional cost for a permit to park on their campus — the price is included in their broad-based fees. Graduate students there pay only $15 a year. Faculty and staff pay a “nominal” fee in order to obtain their permit.

Students at UAlbany pay an annual parking fee of $50 per vehicle. Albany’s site also mentions a “Comprehensive Service Fee” in their broad-based fees, which helps fund their Office of Parking and Mass Transit Services. Even though Albany and Buffalo operate by charging most — if not all — parking fees within their tuition payment, Stony Brook University does not appear to be considering that option. The current status of the MAPS as a self-funded university service is treated as the sole option.

The only SUNY university that holds a candle to Stony Brook’s proposed parking plan is Binghamton — a little over $140 per year, with a significant discount given to GSEU members. None of these other SUNY schools operate using a tiered parking service like the one Stony Brook plans to implement in the fall.

The first question many students at the senate meeting had for MAPS was why, after 30 years, repairs were only just being done now and all at once. Violet’s answer gave little insight — admittedly, she likely doesn’t have much insight on the issue considering she only came to Stony Brook in the fall of 2021. At the union meeting about a week earlier, Speight asked Zacarese a similar question: If hospital workers had been paying about $16.25 a month for 30 years, where had all that money gone?

“He said, ‘I don’t know, I wasn’t part of it,’” Speight said. “But still, you’re accountable because you’re management — you represent management.”

In the face of these deflections, some critics of the proposal ask why the university administration doesn’t help MAPS stay above water. The technical answer is that as a department with an IFR account, MAPS is more or less required to be self-sufficient, never spending more than may make — an IFR account is also pretty much the only reasonable option for organizations on campus that generate outside revenue.

Union leaders pointed out a number of different ways to supplement the cost of repairs without eliminating free parking and sending current parking prices through the roof. Speight suggested that MAPS request a bond from the state. Pacholk claimed MAPS administrators simply don’t want to put the work into applying for community grants that might help them cover the necessary costs.

“There is money for projects like this that exists within both our state and federal government,” she said. “It’s a failure for them to do the work.”

On Wednesday, Feb. 15, a group of students rallied by the stone fountain in front of the Administration Building to protest MAPS’ proposal. Reddit user u/Nuke_bot posted a flyer for the protest on r/SBU, which later gained traction on Instagram — but when the attendees gathered in person, u/Nuke_bot was nowhere to be found. As a result, the protest was “a bit disorganized,” as Matthew Belzer, vice president of SBU College Socialists, put it. It was slated to start at 1 p.m., but this disorganization caused delays.

When it became clear that u/Nuke_bot intended to remain anonymous, students took charge. They wielded cardboard signs atop the fountain’s ledge — one written spontaneously in ballpoint pen declared, “Piss Off Admin!!”

“M-A-P-S, G-T-F-O,” students shouted as they passed around a megaphone. After about a half hour, the number of protestors slowly increased, and they made their way into the Administration Building to continue their demonstration.

Although they didn’t garner as large a showing as they hoped, the College Socialists remained optimistic. “Small numbers still make an impact,” Amanda Basinger, the club’s president, said. “Active action does work, and if you really put yourself to it, you can accomplish change.” Online, the group created a petition against the increased price.

“You have a lot of power you can hold through organization, and coming together to pressure the administration to not enact these changes,” Öner said.

GSEU is now allied with the College Socialists for upcoming protests against “SBU & NY greed.”

CSEA Local 614 is planning an informational day and will invite students, faculty, staff, other unions — anyone who is affected by the parking proposal — to protest the changes. “That’s our best weapon,” Speight said.

The rally is being planned for mid-March — it will take place on the steps between the Administration Building and the Wang Center.

Both CSEA and GSEU emphasized the power of undergraduate students as one of the largest populations on campus.

“We also ask all undergrads to be aware of their power and come stand in solidarity with us,” Öner said.

On Monday, Feb. 27, Stony Brook University President Maurie McInnis sat at the head of a long table, sporting her trademark bright red pantsuit, ready to discuss a multitude of issues with student media. She admitted that the current state of Stony Brook University’s parking is not ideal — “Garages that are, we’ll just say, literally crumbling in front of our eyes.” She briefly noted that USG recently proposed the creation of a student advisory group on parking, but offered few specifics as to who would be invited to participate and when it would occur.

McInnis mentioned the loss of faculty and staff over the years due to the university’s “modest tuition increases.” Since its peak, Stony Brook has reportedly lost almost 100 faculty and 300 staff members as the school has struggled to pay them enough to stay on board.

“You all are starting to feel that, that is really starting to have an impact on your experience,” she said.

However, regarding whether or not the increased prices for parking will have an effect on faculty and staff, McInnis was visibly surprised to be asked such a question, shaking her head to indicate an adamant no.

“I don’t believe that is any concern at all.”

Despite McInnis’ apparent nonchalance, there is imminent cause for concern for the faculty and staff that keep the university running.

“It’s literally the icing on the cake,” Pacholk said. “It’s the straw on the camel’s back… Literally, people are going to leave over parking.”

Rafael Cruvinel contributed reporting. USG, UUP, UUP East and NYSPBA declined to comment.

Correction 3/22/23: An earlier version of this piece incorrectly used data from 2021 to determine the extreme poverty line in Suffolk County, N.Y. This article has been updated to reflect the most recent data on income limits from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Comments are closed.