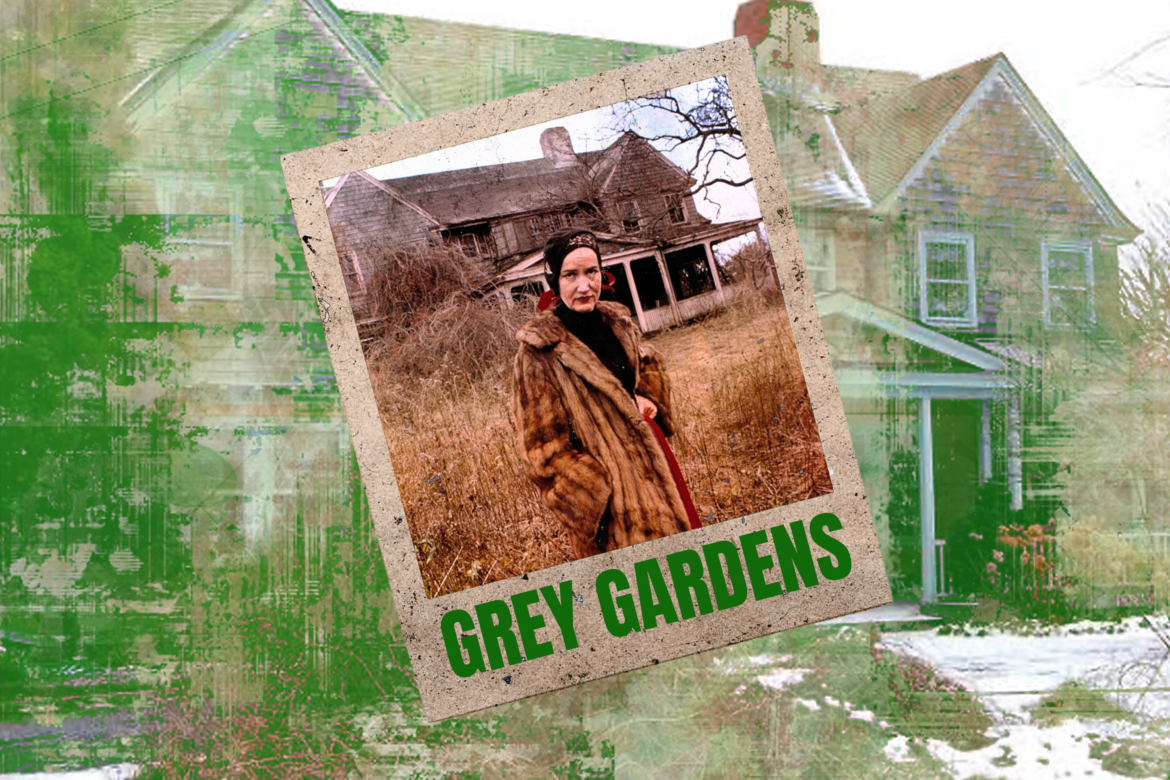

Graphic by Vik Pepaj

In Grey Gardens, Little Edie, wearing white kitten heels, performs her iconic dance in honor of July Fourth. Her shoes appear in frame first, guiding her as she struts down the eponymous estate’s rotting staircase. They are the brightest object in the entire sequence, outcompeting her handheld flag’s white stripes and perhaps only rivaled by her dazed smile.

When she completes her descent, the documentarians, Albert and David Maysles, pan the camera up her body. Little Edie is revealed to be wearing black sheer stockings, a black leotard and of course, a red and blue headscarf, chicly tied in a knot underneath the left side of her chin. She begins to twirl and glide in and out of the frame, testing the adeptness of the cameramen as she unpredictably moves about waving a miniature American flag.

Her dance has come to be one of Grey Gardens’ memorable moments that, like most of the documentary, is construed in both a positive and negative light. Some finish the film and praise it as a story of rebellion against the status quo; two women are fighting against their family and the town of East Hampton for their right to live in solitude in a shambolic home. Others struggle to observe it as a counter-cultural tale and instead view it as a sob story of two women exiled by a world unprepared for them.

Favorite scenes differ amongst watchers as well; some love the bickering between the two women, while others feel their hearts break as battles between Big and Little Edie unfold.

Yet an undeniable appeal of the film is the fashion, particularly that of Little Edie.

To commemorate its 50th anniversary, the Paris Theater in New York City — the same theater where it initially debuted — held a special viewing of the film where jeweler Alexis Bittar, actress Julia Fox and Albert Maysles’ daughter, Rebekah Maysles introduced it.

The event called for homages to be made towards Big and Little Edie. When I stood across the street from the Paris with two friends, we watched the waltz of those entering beneath the dazzling marquis. In Little Edie fashion and Fox’s glamour, our soon-to-be fellow moviegoers donned gaudy headscarves, flowing blouses of a plethora of patterns, cat-eyed sunglasses and the occasional fur coat.

By comparison, my friends and I had agreed to wear all black, incorporating a few touches of our own. One of my companions stood her ground across from the Paris sporting chunky platform boots, wearing a voguish Ulla Johnson dress, tiered with white ruffles around the collar. In a very “Little Edie and her towel headscarves” custom, she reinvented the dress’ purpose as a Wednesday Addams costume for a previous Halloween. My other companion wore a black steampunk vest and black cargo pants, blending the new and the antiquated through his attire — again, in Grey Gardens fashion. I wore a vest emblazoned with buttons, brooches and pins, remembering Little Edie’s incorporation of similar items to jazz up her towel headscarves and towel skirts.

Our fellow attendees’ attire visually reflected an appreciation of the film; Little Edie’s most iconic outfits were recreated throughout the theater. One individual wore a black leotard and black shorts, remembering the debutante’s iconic dance. For every three people who did not wear bandanas or scarves, like my friends and I, there were nearly an equal number of people to make up for the lack of them. So much so that when Rebekah Maysles pranced onto the stage, matching the audience’s eccentric outfits through her own, she commented on “all of the Little Edies in the audience.” The subdued monochrome palettes of my friends and I were mirrored through Fox, who wore a black headwrap held together by a ginormous bow.

Fox, whose introduction I had most anticipated, asked the question that many have after watching Big and Little Edie’s lives unravel: Were the women crazy? And if so, does it matter?

She touched on the poignancy of their story and rebuked the claims of Bittar, who said more than once that the women were alcoholics (there is no proof of this, as Fox defended). By easing us into the experience, she unintentionally prepared us for the offbeat journey of watching an equally offbeat film.

Until this point, I had only watched Grey Gardens twice, devouring its bizarreness both times. But after each viewing, the film left a sour aftertaste in my mouth. Perhaps it was because I could not stomach the idea of feeding raccoons in my attic with stale bread and kibble for cats. It is also a struggle for me to imagine eating corn that I boiled in a bed already contaminated by plates of rotting food. I do not think I could withstand moving about in designer clothes on a floor littered by empty boxes and weeks’ worth of newspapers, actively defending the opulent life I could have had. But this is the life that the women in the film live with a flippant attitude of normalcy. I never finished the film feeling that I had watched a comical story, even though there are moments of humor sprinkled throughout the film.

The moviegoers in Little Edie costumes and the intense clapping when the movie began did not initially appear as a bad omen. Yet as I sat and watched the film, I began to feel that something was awry. Nearly every three minutes, laughter roared throughout the theater. Humor does not seep through every scene, but to an outside observer listening in through the closed theater doors, one might assume it did. As the women bickered on screen, the audience cheered them on; at Big Edie’s birthday dinner with two visibly uncomfortable guests, the audience giggled; when one of the dozens of wild cats living in the home defecated behind a portrait in the women’s bedroom, the audience clapped.

Watching the heads of the jovial moviegoers in front of me tip backwards as they laughed was nearly as uncomfortable as watching the drama unfold on screen. About an hour into the film, the noise was superfluous and seemed mean-spirited. The audience was not laughing with the women, but at them. After the theater lights turned on, it became apparent that garbage had accumulated in the aisles, as popcorn buckets and paper cups drained of soda littered the floor. The Little Edies in the audience flooded the aisles with color, as vibrant headscarves bopped out towards the front doors, leaving Grey Gardens behind and venturing back into the present day.

When my friends and I regrouped, our first discussion centered not around the film itself but the excessive laughter that accompanied it. For all the well-dressed moviegoers, their taste did not translate into their consumption of Big and Little Edie’s story. Instead, the tackiness that was evaded in the costumes transformed into a peculiar viewing of the movie. Although our fellow moviegoers had escaped the Grey Gardens screening unscathed — in fact, they may have left feeling emboldened — we were left pondering how a haunting documentary could be seen through such a distorted lens of humor.

Fox’s initial question — were the women actually crazy — is partly why audiences keep returning to Grey Gardens. When the documentary was initially released, some critics shamed the film as a tale of exploitation, as the women’s lifestyle is undeniably abnormal. We are peering into the strange, dishevelled lives of two women, turning the audience into not just viewers, but voyeurs. Contemporary viewers and the stars of the film — and stars they are — are separated by five decades, but it is imperative to remember that Grey Gardens explores the lives of two women who were victims of their time and, most tragically, of themselves. Little Edie, who repeatedly dresses up to walk around a house that crumbles around her, reminds us that “it’s very difficult to keep the line between the past and the present.”

Her sentiment rang truer than ever amongst the poor taste displayed in the Paris that day.

Comments are closed.