Graphic by Emma Ehrhard

One of Saturn’s moons has been keeping a deep secret — but not anymore. Researchers at the Paris Observatory have discovered Mimas, Saturn’s smallest and innermost major moon, is entirely covered by an ocean. The ocean is hidden under 20 to 30 kilometers of ice according to a study published in Nature, a scientific journal. Researchers estimate the ocean to be around 25 million years old, which is fairly young compared to the rest of the solar system. Studying a younger ocean would provide scientists the opportunity to understand the internal processes and interactions between water and rock on satellites and understand other evolutionary processes behind satellite formation.

Researchers have been interested in Saturn and its 146 moons for a long time: Mimas was first spotted in 1789 by English astronomer William Herschel. What used to be a speck in astronomers’ telescopes is now full-sized and clear thanks to the help of the Cassini-Huygens spacecraft. Cassini’s production was a joint effort between NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency. Cassini, launched in 1997, provided data on Saturn and its rings and moons for 13 years until the spacecraft crashed into Saturn’s atmosphere because it ran out of fuel. Despite the spacecraft’s unfortunate ending, researchers had a gold mine of data at their disposal, and were able to delve into the geophysical makeup of Mimas and draw new conclusions about its terrain and subsurface ocean.

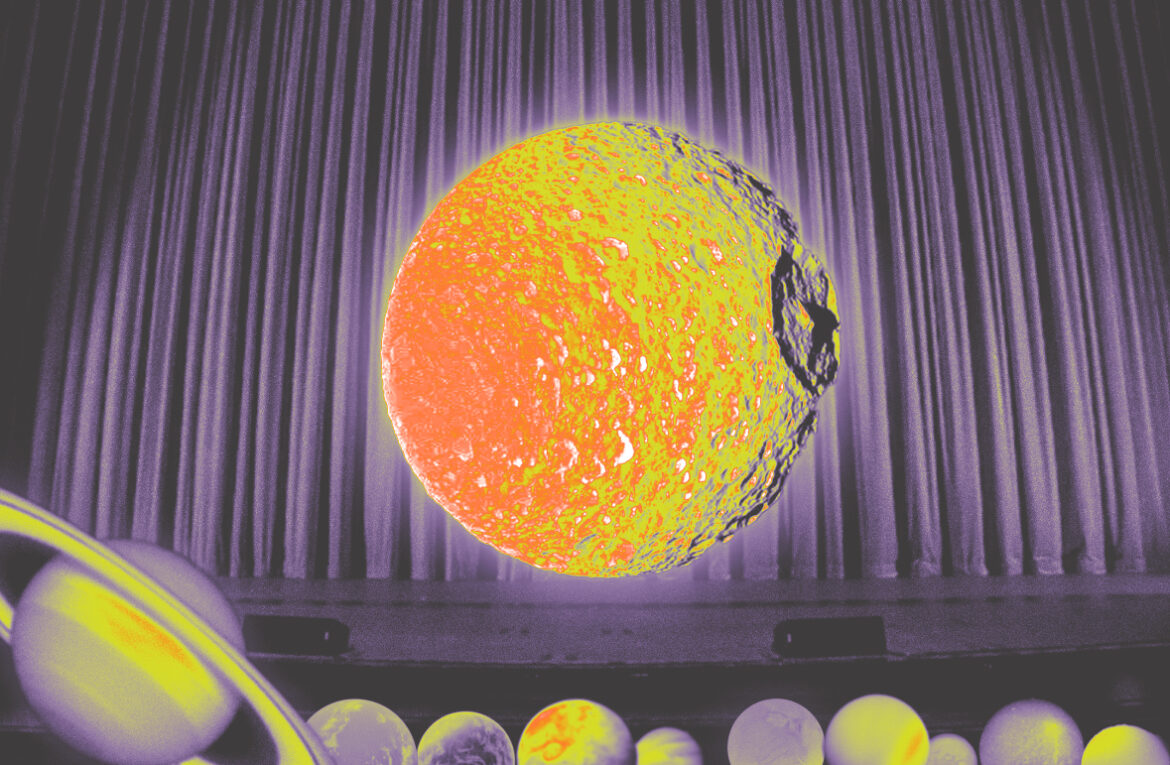

Mimas is often nicknamed the “Death Star” due to its gray and white exterior — which resembles the Star Wars space station. Dr. Valéry Lainey, an astronomer at the Paris Observatory and one of the authors of the study, was excited by his team’s discovery.

“We already had the feeling that Mimas could be a very different moon, not rigid and cold as it looked like,” Lainey said. “We were very optimistic … and now, we can really claim this as a global ocean.”

Oceans on moons are nothing new to scientists. In fact, some of the moons orbiting Jupiter, Uranus and Neptunes are suspected of having ocean landscapes, creating potentially habitable environments for microbial life.

“These oceans that we’re finding on worlds in the solar system … have the same conditions that formed life on Earth, and maybe what we call habitable environments,” Bonnie J. Buratti, a senior research scientist at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory who was not associated with the study, said. Buratti is also the deputy project scientist for NASA’s Europa Clipper mission, a mission to Jupiter’s moon, Europa, which also has a global ocean suspected of containing life. But if researchers are already aware of oceans on distant moons, what makes Mimas different?

Mimas is 115,000 miles away from Saturn and completes its orbit around the planet in just 22 hours and 36 minutes. Because of its proximity to Saturn, Mimas is expected to have a higher internal temperature than the rest of Saturn’s moons due to tidal heating. This heating occurs when the strong gravitational pull of a massive planet pulls on the orbits of its surrounding satellites and stretches them. This creates internal friction that generates massive amounts of heat. Still, Mimas has 20 to 30 kilometers of ice on its surface. This is perplexing to researchers. Mimas should be geologically active and scorching hot, but instead, it is frozen over with ice.

Compare this to Enceladus, another one of Saturn’s moons that is 148,000 miles away from it. Because it is farther from Saturn, Enceladus is expected to experience lower tidal heating — but this is not the case. Researchers have observed geysers on Enceladus spewing hot water. “Trying to figure out why Mimas doesn’t look geologically active is odd. These are two objects that you’d think would behave in the opposite way they’re behaving,” Matthew Hedman, an associate professor of physics at the University of Idaho who was not a part of the study, said. Hedman studies the structure, composition and dynamics of Saturn’s various rings, and he is also involved in the Europa Clipper Mission.

Lainey believes the reason for Mimas’ icy exterior is simple: heat from Mimas’ core has not dissipated enough to melt the thick layer of ice at the top, which is why there have not been observations of geological activity. While the inside of Mimas remains hot, space’s subzero temperatures are keeping the outside layers frozen. “Space is extremely cold,” Lainey said. “This friction will provide heating inside Mimas. The core is getting warmer and the part of the ice that is more tight with the core also gets melted, and this is how [Mimas] will start to melt from the interior, creating this ocean.”

But that’s not the moon’s only oddity. Researchers have observed the roundness of Mimas’ orbit and found that it was very eccentric, or non-circular. This poses another question. Oceans are supposed to “stabilize” a satellite’s orbit by making them more circular. So how could there be an ocean on a moon with an eccentric orbit? The authors of the study reasoned that the ocean was formed recently.

“If this ocean was around for a long time, the eccentricity would have collapsed back to zero,” Hedman said. “It’s not zero, it’s big.”

Mimas’ eccentricity might be due to multiple factors, such as its unequal distribution of mass, or Saturn’s powerful gravity tugging on its orbit. Some scientists think there is more to the story.

“Maybe something is going on inside Saturn that we don’t fully understand that is pumping up Mimas’ eccentricity,” Hedman said. “There’s a lot going on with the satellite and ring system that doesn’t quite make sense yet.”

Other researchers believe that there has not been enough research on Mimas yet to confirm or deny the claims of its ocean. “It’s harder to study the inner moon[s] because the spacecraft has to get pretty close to Saturn,” Buratti said. “Maybe we haven’t been close enough.”

Despite some uncertainties, researchers are interested in determining the geological makeup and evolutionary history of these icy moons. Researchers like Hedman are excited that there is still so much work to be done regarding the four outer planets and their satellites. “We’ve got pieces of the idea but it hasn’t formed into a coherent picture,” Hedman said. “It’s exciting because it means there’s stuff to actively learn.”

Lainey hopes that his team’s discoveries will persuade other scientists to look deeper than the surface of satellites that may not appear to have life. “An object can look like a completely dead object, [but] it does not necessarily mean that you don’t have habitability inside,” Lainey said. “I’m sure [Mimas] also might motivate further analyses of solar system objects that don’t look habitable.”

Comments are closed.