By Sophie Beckman and Melanie Formosa

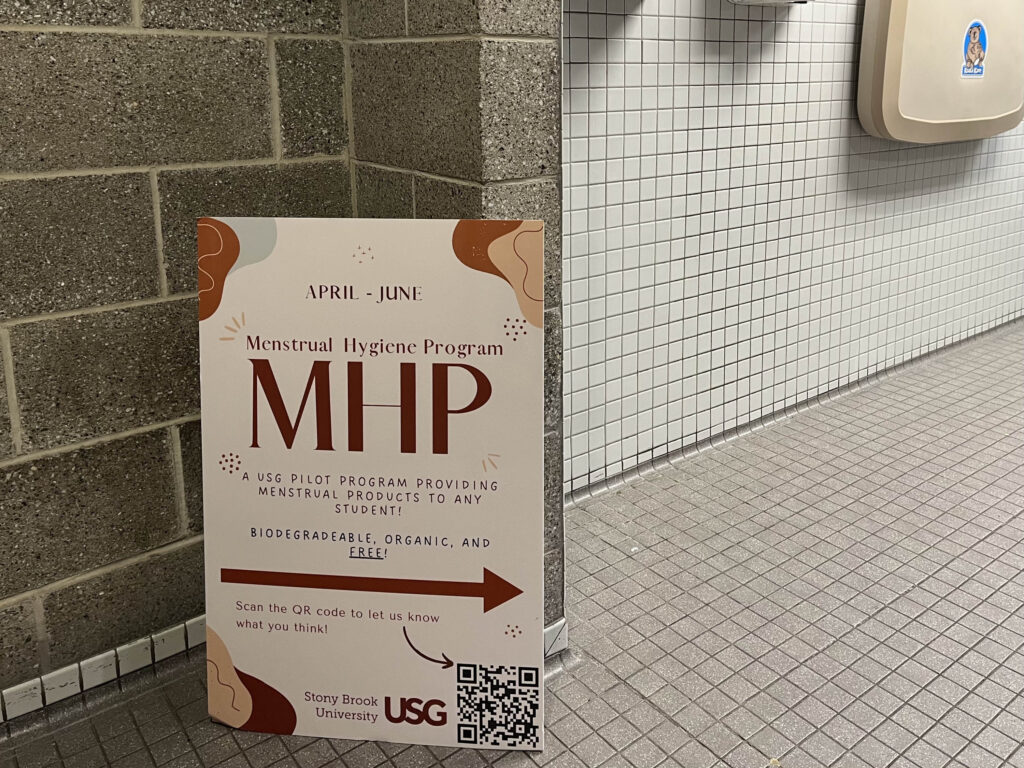

Stony Brook University’s Undergraduate Student Government (USG) recently launched a pilot program to provide free menstrual hygiene products to students on campus, called the Menstrual Hygiene Program (MHP). While the name suggests a solution to the lack of access to products on campus, it is not enough.

This program consists of only two product dispensers across the entire campus — which has a student body population of over 25,000 — and both product dispensers are located in a single location: the Student Activities Center (SAC).

This initiative took two years to be approved, and it is funded solely by the Student Activities Fee, which is already split between all clubs and activities on campus. This sparse funding is one explanation as to why the dispensers are located in so few bathrooms.

Stony Brook students are never expected to pay for their own personal toilet paper in residence halls or class buildings. As menstruation is another basic human function, there should be no cost for period products either. This disparity affects students’ physical, mental and emotional health, and puts a financial strain on students.

Acknowledging the issues around menstruation starts with fighting the mindset that period products are luxury items that should be dealt with personally. Normalizing discussions about menstruation can create a shift in this archaic perception. Companies like Aunt Flow, which has partnered with Stony Brook for the new MHP, are working to start the conversation and advocate for free period products.

“Policy change comes with cultural change,” Anusha Singh, a community and impact specialist with Aunt Flow, said. The lack of availability of products is not purely because of a lack of funding.

“There is always a budget for toilet paper,” Singh said. “Even if the student population were to triple in size, schools would never require students to purchase their own toilet paper. Because of the stigma around menstruation, and the fact that non-menstruators are usually the majority in administration, period products are not seen as a priority.”

Lack of access to products is a widespread and pervasive issue among students. According to a 2021 study by Thinx, students often struggle to afford period products and rarely find free products in school bathrooms. Students at Stony Brook are no different.

Multiple students on campus haven’t seen that there are now free products in the SAC bathrooms. Madison Ford, a junior at Stony Brook, was surprised to hear that products are located there now.

“The other day my friend got to class and realized she forgot tampons. She had to walk 15 minutes back to her dorm to get them,” Ford said.

This scenario is not rare, and students often miss valuable education because they don’t have access to period products. This impact on attendance and performance can be seen across school campuses. According to the Thinx study, “65% [of students] do not want to be at school when they have their periods. 38% often or sometimes cannot do their best schoolwork due to lack of access to period products.”

“We don’t get a choice when we have our period or if we have one at all. It’s unfair to have to pay to begin with,” Ford said.

Even students who have seen this initiative in practice want greater availability of products on campus.

“I don’t always have products on me,” Erin McCartney, a junior, said. “That could happen anywhere, and then you’d have to walk to find something.”

Prior to this pilot program, very few locations on campus offered free period products. Students in need of these products were limited to baskets in the lobby of the Campus Recreation Center, outside the Center for Prevention and Outreach offices and inside the LGBTQ+ Center.

Lamisa Musarat is the associate treasurer of the Undergraduate Student Government. She helped to initiate the new Menstrual Hygiene Program on campus and surveyed the student population.

“People feel uncomfortable getting products in public locations,” Musarat said. “These resources, like in the Rec, were rarely used by students.”

A goal for this program is to provide dispensers directly inside bathrooms in other high-traffic areas including the Melville Library, the Student Union and eventually in residence halls, Musarat said.

Other schools have proven that with enough advocacy, these programs can be implemented campus-wide. The University of Michigan has over 2,000 restrooms stocked with free menstrual products following requests from students to make the products available. After California’s Menstrual Equity for All Act passed in 2021, universities across California are now advised to stock at least 50% of their bathrooms with free products. UCLA supplies all campus restrooms with menstrual-care products.

During the launch event for the Menstrual Hygiene Program, Musarat shared student feedback about the affordability of products.

“Menstrual hygiene products should not be priced the way they are in the marketplace on campus,” one student surveyed said. “That is unethical for a product that is necessary for half the population.”

At a market on campus, one box of ten tampons costs $8.63. According to calculations done by The Huffington Post, those who use tampons go through about 20 per menstrual cycle. Cycles vary and could require more or less, but in general, this means that at Stony Brook University, it costs students about $17 a month and over $200 a year to sustain a basic biological function.

“Don’t make students put in money for a basic human necessity,” another student who provided feedback on the new pilot program said. “This is long overdue.”

When students are forced to pay upwards of $200 per year on products, they are more likely to resort to reusing products or finding alternatives. Rachel McFarland, treasurer of Planned Parenthood Generation Action (PPGA), spoke at the MHP launch event about this issue.

“Lack of access has been linked to using substitute products, like toilet paper, socks, two pairs of pants and stretching product usage,” she said.

Extending the life of period products may result in risks for vulvar irritation, vaginal discomfort and fatal toxic shock syndrome. According to research by Huma Farid at Harvard Medical School, 64% of people who menstruate in the United States reported having difficulty affording menstrual products at some point, and 21% reported they were unable to afford menstrual products every month. Food stamps and subsidies under the Women, Infants and Children (WIC) program do not cover the cost of menstrual products.

In addition to their financial strain, menstrual products strain the environment. The typical disposable pad takes roughly 500 to 800 years to decompose, and is used by 89% of people who menstruate. A person who menstruates will use between 5,000 and 15,000 pads and tampons and 400 pounds of menstrual hygiene product packaging in their lifetime, and disposable menstrual products contribute to the over 250 millions tons of trash that Americans generate each year. The $2-billion-per-year menstrual hygiene industry commercializes the natural menstrual process and appeal to environmentally conscious consumers with buzzwords like “compostable” or “biodegradable,” but often these products still contain plastic for waterproofing.

Stony Brook’s partnership with Aunt Flow offers a slightly more environmentally conscious option, producing approximately 25% less waste than leading brands due to being made with 100% organic cotton. Despite this, the location of these products is restricted to only two dispensers in the SAC, so any positive environmental impact is minimal when the rest of campus continues to use traditional disposable products.

Stony Brook students are working hard to advocate for accessible products on campus. Clubs like End the Stigma SBU, PPGA and the LGBTQ Alliance are leading the charge in spreading awareness about issues surrounding periods. A big issue that these clubs focus on is period poverty, or a lack of access to menstrual products, for college students and for people around the world.

A major contributor to period poverty is the “luxury tax” collected on menstrual products in at least 30 states in the U.S. The menstrual product tax exacerbates period poverty because it acts as a barrier to the estimated 16.9 million menstruating individuals across the country living in poverty.

Statewide policies have been put in place for no-cost menstrual products in public bathrooms. In 2018, former Governor Andrew Cuomo signed a bill that requires public schools in New York to have freely available menstrual products for grades 6 through 12. But for public universities and colleges in New York, the requirements remain unclear.

New York Assembly member Linda Rosenthal has introduced a new, more inclusive version of this law called the Total Access to Menstrual Products, or TAMP, Act. The proposed law would require tampons and sanitary napkins to be available in all public restrooms across the state, including universities. It is currently active in the assembly committee and has to be passed by the Senate before it can be sent to Governor Hochul.

The main barrier to implementation of these policies stems from the fact that menstruation is seen as taboo, and those in charge are unlikely to prioritize providing free products if they aren’t aware that barriers to access exist. With more awareness and advocacy, period poverty could inch its way to the forefront of policymakers’ agendas.

Students on campus are continuing to push the importance of this issue. The lack of access to free period products at Stony Brook is a source of unnecessary financial stress and a barrier to learning in a university that prides itself on providing an “accessible world-class education.”

Comments are closed.