Smoke engulfing the room. Dark pieces of hair circling the white tiled floor. The smell of burning and chemicals. The salon was sandwiched between a laundromat and a bodega defaced with graffiti. On Sunday mornings for 11 years, I got my hair straightened there, sitting in a leather chair and flinching at the burning and blistering heat against my scalp. The pain was necessary to conceal my natural appearance.

Pelo malo, which literally means “bad hair,” was a constant refrain in my home. The term is part of what it means to be Dominican, yet it was meant to be an insult. Naturally, my hair is a bed of unruly dark brown ringlets, unmanageable and dense. When I bathe, thick strands collect in my bathtub. The weight of several thousand curls means never being able to properly tie my hair — because gomitas, hair ties, would always pop on the first attempt to get them around it all.

Meanwhile, pin-straight hair was always the hallmark of beauty. When I watched Telemundo or television commercials, I saw news anchors and models with that look — never anyone with hair like mine. Having straight hair seemed to be society’s standard of beauty and acceptance, while anything contradictory was automatically deemed ugly and alien.

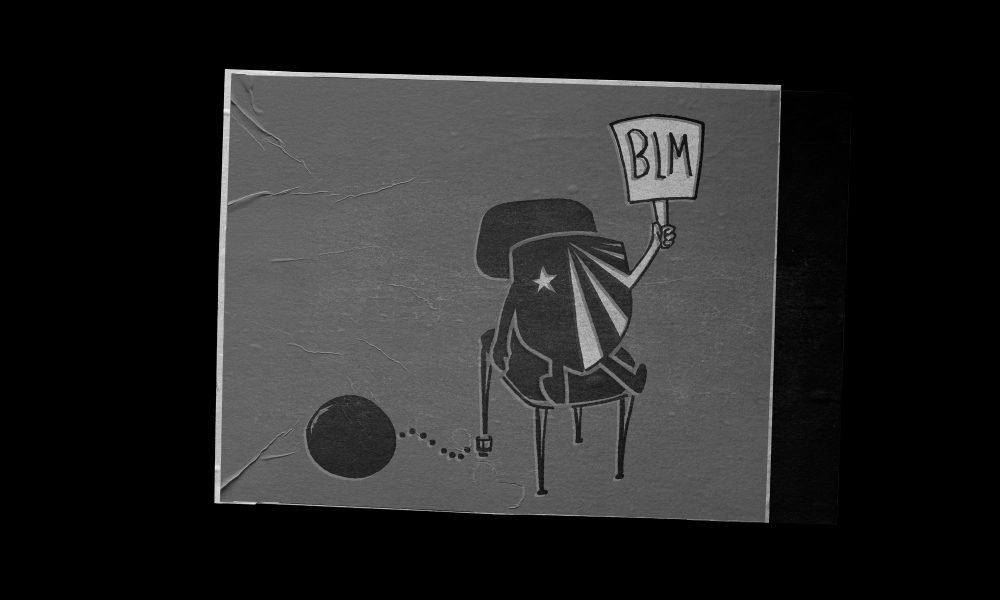

The salon was my gateway to this ideal. The straightener was my ticket to America’s concept of beauty. At the salon, I created the presentable version of myself. Sundays were for assimilating. Sundays were for erasing part of myself.

In elementary school, having straight hair meant an overflow of compliments and Can I touch your hair? moments. It was the ultimate vindication of my Sunday routine: My sleek and manageable hair meant that I could finally be recognized and admired. I finally resembled those girls on television. I became obsessed with conforming to these ideals, in ways that made me reject the most obvious form of my heritage by passing a hot comb through my culture.

On days I couldn’t afford to visit the salon, the air around me felt more enclosed and the looks were no longer in admiration. But your hair was so pretty straight! classmates would tell me. I struggled with recognizing the beauty in my natural hair because of its stigma, but also because of the absence of successful women of color in traditional media outlets.

But social media changed everything.

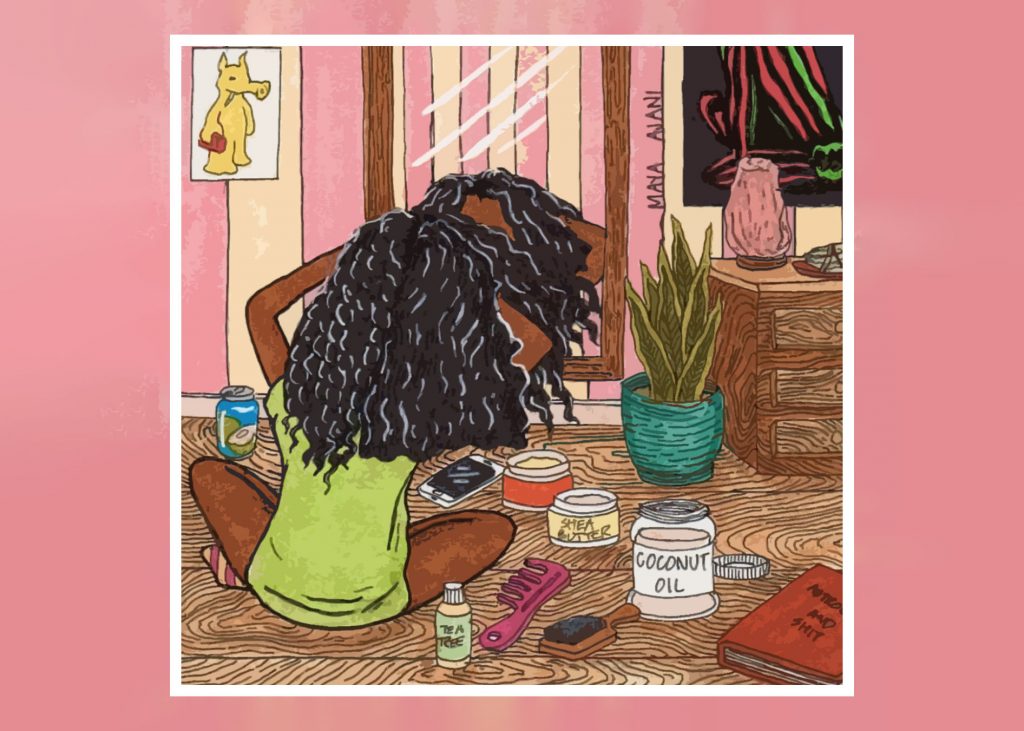

Across newsfeeds and timelines, there were women that shared my same skin complexion and my unruly kinks. For once, I saw myself in these women, who might have also struggled with their own appearance. They were unapologetic and proud of their identities, encouraging natural coils as they celebrated being people of color. I traded in my straightener for a curl activator cream. I traded in my fears of not being taken seriously for celebratory feelings of proudly wearing my culture.

My hair is now in a transitioning state. The damaged ends are obvious, yet so are the ringlets. The way my hair curls at the top but remains straight on the ends is a reminder of the 13 years that I spent trying to erase parts of myself. Through the transition, I’ve learned to embrace my kinky roots, and what it means to be Dominican in a world that only praises straight and manageable hair. Taking ownership of my natural identity forced me to differentiate myself from society’s perceived norms. My transition is empowering for me: It lets me wear my culture freely without fear of judgment. The curls, the coils and the kinks are all parts of what it means to be Dominican.

Comments are closed.